By Ayesha Nasir, Karachi, Pakistan

I have something in common with Omar Khadr. We are both fans of “The Hunger Games” – the best-selling trilogy by Suzanne Collins. One of the most obvious differences between us is that I have not spent ten years of my youth in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

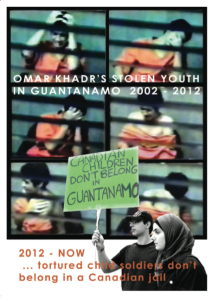

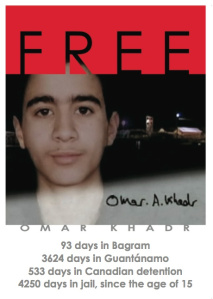

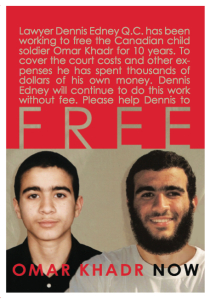

As a 15-year-old, Omar Khadr was captured by the US Armed Forces in Afghanistan, when he was wounded twice in the back in a fire fight, which broke out in July, 2002. It was alleged that the teenager had killed a US Special Forces soldier during the fire fight. He had been in an Afghan compound, where he was a translator for his father’s acquaintance. From eastern Afghanistan, Omar was taken to Bagram in a critical condition; he had sustained wounds, which lead to “three holes in his body” and “shrapnel in his face”.

The native-born Canadian remained in the US custody for ten long years, during which his family and activists all over the world pressured the Canadian government to “bring him home”. Heather Marsh, a journalist vocally supporting Omar Khadr’s release, pointed out how “it is legal for US soldiers to kill children”, whereas “it is a war crime for children to kill US soldiers”, raising a valid concern about the double standards, which led to Omar Khadr being alleged with a war crime in the first place.

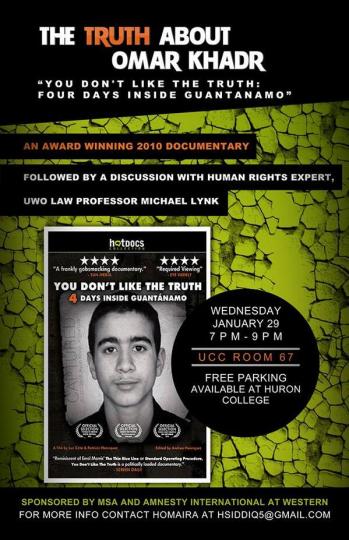

Omar Khadr’s imprisonment was handed out despite compelling evidence, which stated otherwise, while the United States and Canada ignored the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict (to which they are signatories) and went ahead with his imprisonment. It was eight years later, in 2010, that the Canadian Supreme Court acknowledged the blatant abuse of Omar’s rights as a human and as a Canadian; the interrogation, which the Canadian Security and Intelligence Service (CSIS) made the “detained youth suspect” undergo was regarded as “a clear violation of Canada’s international human rights obligations” by the Canadian Supreme Court, who is known for its apparent impartiality and execution of justice.

At the time, Audrey Macklin, a professor in the Faculty of Law at the University of Toronto, wondered if the verdict of the Supreme Court of Canada on (a) that the government has violated Khadr’s Charter rights”, and (b) that Canada “should seek repatriation”, was “not enough to motivate this government to act” then there was no saying as to “what is enough to motivate this government to do the right thing”.

“I cried several times during the interrogation as a result of this treatment and pain. During this interrogation, the more I answered the questions and the more I gave him the answers he wanted, the less pain was inflicted on me. I figured out right away that I would simply tell them whatever I thought they wanted to hear, in order to keep them from causing me such pain” – from Omar’s affidavit statement on February 22, 2008.

Testimonies from other prisoners, such as Moazzam Begg, give detailed reports on the treatment he was made to undergo; David Hicks, an Australian prisoner, declared that he “saw US soldiers dragging Omar from his cage to a room used for interrogation just opposite from mine. For at least an hour, I heard him scream and yell in pain as they abused him. Omar was yelling, ‘Why are you doing this? … Please stop. … Somebody help me!’ There seemed to be no point to this brutality except to hurt him and break his will.”

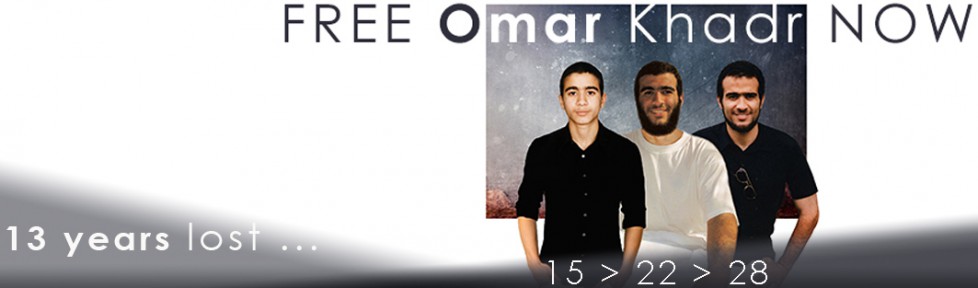

It appears that living in the black hole for human rights did not break Omar’s spirit, for he was sent home to Canada on September 30, 2012, where, as of now, he remains incarcerated in a maximum security prison. Andy Worthington, a journalist, who has been following Omar Khadr’s case closely, admits that the Canadian government could keep him in custody for roughly half a decade more; an outcome of a plea deal made in October, 2010. Despite how reports on his case acknowledge his good behaviour during his ten-year imprisonment, parole remains nowhere near until at least 2015. After having spent considerable time with him, two of Omar Khadr’s US military lawyers describe him as “an intelligent young man” who possesses a “love of learning”.

This “love of learning” has been explored by Arlette Zinck, a professor of English at King’s University College in Edmonton, who took up the task of designing and delivering a study plan for Omar Khadr, while he was detained at Guantanamo Bay. The coursework assigned to him was something he pursued eagerly, a clear sign of a young mind being freshly exposed to a world of literature. As a teenager myself, I do not find it surprising, when interaction with Professor Zinck revealed that Omar identifies most to the character of Primrose Everdeen in “The Hunger Games” trilogy, regarding her as the “moral centre” of the story. Through correspondence via letters and classes held inside prison, Zinck notes a “remarkable” thing about her unique student that regardless of his “exceptionally difficult circumstances”, he manages to find “a way to stay positive and hopeful when many grown men would not.” This is depicted in the “impressive” levels of “energy and determination he puts into his studies”.

Unpopular belief will see Omar Khadr as a political pawn in history by those, who wanted to justify and escape from their criminal actions. There are people, who view Omar Khadr as a radicalized terrorist; despite him having served more than his sentence under an unfair trial, they refuse to allow him to walk as a free man. The boy who will “forever be a murderer” for many is now a young man of 26, whom they do not want to walk as a free man, pursue his education, put his past behind him or even reunite with his family. Being a child soldier, who has been consistently deprived of the most basic of his rights, has put Omar Khadr in a unique position in history, the likes of which were seen somewhere around the second World War.

True rehabilitation, however, is a psychological experience, which will require efforts on the part of Omar, his family, supporters and legal team – the wounds left by the US military penal system will take time to heal. Rehabilitation is part of Corrections Canada’s philosophy and the attempt by the Professor Zinck and Omar’s legal team depicts, how false are the distortions surrounding Omar Khadr. His portrayal in the media is polarized, and, as Pakistanis, who can know better than us about the media’s role in electing the bad guy in the tale. The debate rages on the morality of acts done in the name of love and war, but as we have seen in the case of Omar Khadr, nothing was ever fair.

A decade ago, I was sitting in my school’s library watching “Dumbo” (1941), a Disney classic, and hiding tears over the imprisonment of a baby elephant’s mother, just because she was trying to protect him and appeared a threat while doing so. That is when it struck me: the bad guy in the tale is not always the one everyone points out to be. From this childhood lesson, I have learnt that although the true justice may never be handed out, it is not futile to pursue it. The struggle of the human spirit to resist injustice is a real one; the efforts of conscious individuals, who seek to bring pain to a closure, will echo in the pages of history for those ahead, who will look back and wonder, why there was so much silence for so painful a wound.

“About myself, what can I say? We hold on to hope in our hearts and the love from others to us and that keeps us going until we reach our happiness” – Omar Khadr to Arlette Zinck, in a letter dated January 22, 2009.

.

Source: Hiba Magazine | Hope you are okay, Omar Khadr

Like this:

Like Loading...

DONATION BUTTON: < PLEASE HELP FUND THIS AWARENESS TOUR FOR OMAR KHADR>

DONATION BUTTON: < PLEASE HELP FUND THIS AWARENESS TOUR FOR OMAR KHADR>