The Committee welcomes the recent return of Omar Khadr to the custody of the State party. However, the Committee is concerned that as a former child soldier, Omar Khadr has not been accorded the rights and appropriate treatment under the Convention. In particular, the Committee is concerned that he experienced grave violations of his human rights, which the Canadian Supreme Court recognized, including his maltreatment during his years of detention in Guantanamo, and that he has not been afforded appropriate redress and remedies for such violations. The Committee urges the State party to promptly provide a rehabilitation programme for Omar Kadr that is consistent with the Paris Principles and Guidelines on Children Associated with Armed Forces or Armed Groups and ensure that Omar Khadr is provided with an adequate remedy for the human rights violations that the Supreme Court of Canada ruled he experienced.

- Committee on the Rights of the Child [1]

Between 1983 and 2005, some 20,000 Nuer and Dinka boys – dubbed the ‘Lost Boys of Sudan’[2] – aged between 7 and 17 years, were orphaned, displaced and forcibly conscripted due to the Sudanese Civil War. Emmanuel Jal,[3] now a famous musician, was recruited along with his father by the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army at the age of seven, after his mother was killed by Government forces. Although Street Kids International, a Canadian NGO funded by UNICEF, helped reunite and rescue 150 ‘Lost Boys,’ an overwhelming 17,000 remained in refugee camps,[4] leading eventually to a United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, UNICEF, and US joint venture resettlement program that saw over 4000 boys immigrate to the US.[5]

In 2007, Ishmael Beah, then 27 years old, captivated America with A long way gone: Memoirs of a boy soldier[6] in which he narrates his journey of being forcibly conscripted into the Sierra Leonean Government army at the age of 13 to fight against the Revolutionary United Front - a rebel group. After three years of fighting, killing and severe drug abuse, 16 year old Beah was rescued by UNICEF and placed in rehabilitation, before finally immigrating to Brooklyn, New York, USA in 1998.

Like the US, Canada is a global advocate for children’s rights. A case in point is that of Michel Chikwanine, a former child soldier from the Democratic Republic of Congo, who arrived in Canada as a refugee in 2004. Today, Chikwanine is an accomplished motivational speaker, travelling throughout North America to address the issue of children who are forced to fight in adult wars.[7] Chikwanine’s case contrasts with that of another child soldier, the Canadian citizen Omar Khadr. Canada should have done far better to ensure Khadr’s repatriation to Canada pursuant to its obligations under domestic and international law.

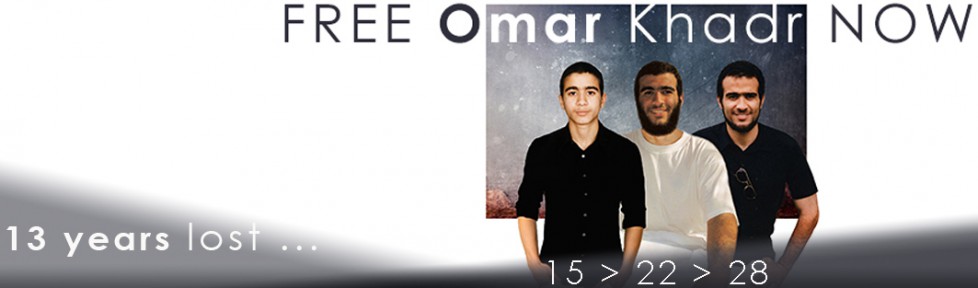

Omar Khadr, the fifth of seven children, was born on 19 September, 1986 in Toronto, Canada to Egyptian-Canadian immigrant parents. In 1996, his father, Ahmad Khadr was accused of involvement in a terrorist related bombing of the Egyptian Embassy in Pakistan. Ahmad was arrested but later released. After the 9/11 attacks in the US, Ahmad Khadr’s name was placed on an American list of suspected terrorists. On 27 July 2002, at the age of 15, young Khadr was caught up in combat between US troops and insurgent forces in Bagram, Afghanistan.[8] As the only survivor ‘brutally attacked, wounded, shot in the back and captured,’ [9] young Khadr was arrested and accused of war crimes including throwing a grenade that killed Sergeant Christopher Speer – a Delta Force soldier/medic.

An affidavit prepared by Khadr [10], along with the findings of the Canadian Federal Court in a case ordering the release of portions of Canadian Security Intelligence Service interviews conducted with Khadr in Guantanamo [11], and the Supreme Court’s decision inCanada (Justice) v Khadr (2008 SCC 28), support allegations of abuse, torture and Canada’s willful neglect of the young Canadian. He maintained his innocence for ten years – but with no end to his detention at Guantanamo in sight, he signed a plea bargain in October 2010, waiving his rights in exchange for an additional eight years in prison – some of which could be served in Canada.[12] Although the Supreme and Federal Courts of Canada (as stated above in the Report of the Committee on the Rights of the Child) recognized clear violations of Khadr’s human rights, the Canadian government refused to take effective measures to bring Khadr to Canada for rehabilitation, unlike (adult) citizens from other Western Countries who were detained with him at Guantanamo Bay.

Interestingly, upon Khadr’s eventual return to Canada, Minister of Public Safety, Vic Toews maintained that ‘Omar Khadr was not acting as a child soldier when, at 15 years of age, he threw a grenade that killed U.S. Sgt. 1st class Christopher Speer. He is a known supporter of the al Qaeda terrorist network and a convicted terrorist.’[13] The mere fact that Khadr agreed to plead guilty to charges of murder, conspiracy, terrorism, and spying, after years of torture and abuse at Guantanamo Bay, is telling. Arguably, Khadr’s Constitutional rights are invoked. According to section 7 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms 1982, ‘Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of the person and the right not to be deprived thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice’. To this end, the Canadian government, cognizant of Khadr’s age, coupled with historical records of torture and abuse, was bound to ensure Khadr’s return to Canada.[14]

The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (hereafter CRC) is the most widely ratified human rights treaty. With the exception of two countries, the US and Somalia, the CRC can boast of 140 ratifications and 193 signatories. In addition to defining a child as ‘every human being below the age of eighteen years unless under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier’ (article 1), the foundation of the CRC is spelled out in articles 2(1) and (2) which state that member states should not discriminate in protecting children’s rights, especially those children who are victimised as a result of parents’, legal guardians’ or family members’ actions or behaviour. Other articles of particular relevance to Omar Khadr’s case include article 37 (protection against cruel, inhuman, degrading treatment or punishment and unlawful arrest); article 38 (states parties’ respect for international humanitarian law in armed conflict, including not recruiting children below the age of 15); article 39 (provision of rehabilitation programs to reintegrate child victims back into society); and article 40 (children should not be accused of infringing a penal law that is not prohibited nationally or internationally at the time the said acts/omission were committed).

A point worth noting is that, thirteen years after the CRC was established, article 38 was amended by the Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict, with Canada the first signatory. The Optional Protocol requires states parties/armed groups to refrain from forcibly or coercively recruiting children under 18 (articles 1, 2, & 4).

In defending the provisions of the CRC, UNICEF Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict, Ms. Radhika Coomaraswamy, issued a statement on the occasion of Omar Khadr’s trial before the Guatanamo Military Commission on 10 August 2010:

All of us interested in the welfare of children, including my colleague Anthony Lake, the Executive Director of UNICEF have argued against children under the age of eighteen being tried for war crimes. The statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) makes it clear that no one under 18 will be tried for war crimes, and prosecutors in other international tribunals have used their discretion not to prosecute children. Since World War II, no child has been prosecuted for a war crime. Child soldiers must be treated primarily as victims and alternative procedures should be in place aimed at rehabilitation or restorative justice. Even if Omar Khadr were to be tried in a national jurisdiction, juvenile justice standards are clear; children should not be tried before military tribunals…The United States and Canada have led the way in creating and implementing these norms…I urge both governments to come to a mutually acceptable solution on the future of Omar Khadr that would prevent him from being convicted of a war crime that he allegedly committed when he was child. [15]

The complexity of Khadr’s case is apparent in SR Coomaraswamy’s statement – the US is not party to the CRC, hence cannot be responsible for its violation. Even the sheer thought of transferring rights, duties and responsibilities between Canada and the US under international law is inherently a ‘mind twister’. Firstly, both countries are governed by separate legal jurisdictions. Canadian laws cannot be enforced in the US, so Khadr’s repatriation depended not only on the Executive Branch of the Harper Government but also on the US Military Tribunal’s resolve to prosecute a minor as an adult for allegedly committing war crimes in Afghanistan. Secondly, even though Canada is party to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, the US is not – a situation that wrinkles the efficacy of enforcing international law. Notwithstanding, there is a common denominator apparent in both Canada’s neglect and the US abuse of Khadr’s rights. In terms of assigning responsibilities to states for failure to protect Khadr’s rights as a minor caught up in conflict orchestrated by adults, the relevant provisions of the Geneva Convention and the CAT (which establishes the rules of war and humanitarian treatment of those caught in war) could be invoked. Yet, the question remains, by whom, where, and when should these provisions be applied?

As stated earlier, Canada has played an advocacy role in relation to the protection of children in armed conflict. According to the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development (DFAIT),[16] Canada not only hosted the first International Conference on War-Affected Children in 2000, galvanising support from the international community to address issues of children and armed conflict; but its government also played a strong role in the creation and negotiation of the Optional Protocol to the CRC and was an early supporter of the Office of the Special Representative for Children and Armed Conflict. Canada’s leadership role in this regard appears to be incongruent with its laissez faire attitude towards young Khadr. One can’t help but presume that Khadr’s religious and cultural upbringing, coupled with ongoing bias and stereotypes which mean the ‘war on terror’ is synonymous with a ‘war against the Muslim faith’, were determining factors in the outcome of this boy soldier’s story.

Reflecting on Khadr’s case makes my first visit to the Supreme Court of Canada in 2006 well up in my mind. I remember being intrigued and captivated by the two magnificent emblems of justice and equality that adorn the front visage of this highest court of Appeal: the Statue of Veritas and the Statue of Justicia. Veritas is the Roman goddess of truth andJustitia is the Roman goddess of justice. Blindfolded Lady Justice, as she is euphemistically referred to, is seen with a scale and a double-edged sword which personifies balancing fairness and reasoning in justice irrespective of one’s race, religion, sex, class, or political opinion.

Still mesmerized with the architecture of this isolated building in Ottawa, I rationalised, the Supreme Court of Canada (the pinnacle of the Judiciary) epitomises protection and the safeguarding of individual rights and civil liberties, and this was vindicated in Khadr’s case. Without a doubt, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, on its face, promulgates protection and security of the person, advances the doctrine of the separation of powers, and upholds judicial independence. Primarily, it is these carefully inscribed words that provide confidence and authority to contest conflicts and ensure accountability for the Executive Branch’s decision to refuse Khadr’s return to Canada. While the Supreme Court was unable to compel the Executive Branch to repatriate Khadr, they did recognize that his rights had been violated. Thus, one hopes that in a free and democratic society, everyone is subject to a rule of law which upholds equality, justice and fairness. The fact remains though: the US and Canada continue to provide a safe haven for many child soldiers from Africa; yet for Omar Khadr, the stakes were different. In case you are wondering where to find evidence of terrorism, torture, and war crimes here are some pointers:

- Abukar Arone and Dahabo Omar Samow by their Litigation Guardian Abdullahi Godah Barre v. the Attorney General of Canada (unreported, 6 July 1999, Ontario Superior Court of Justice, Cunningham J.).[17]

- The White House Torture Memos: Memo of John C. Yoo and Robert J. Delahunty, Office of Legal Counsel, Department of Justice, to William J. Haynes, II, General Counsel, Department of Defense, ‘Application of Treaties and Laws to al Qaeda and Taliban Detainees’, and Yoo’s Memo on Avoiding the Geneva Convention Restrictions, 9 January 2002.[18]

- An Inquiry into the Actions of the Canadian Military in Afghanistan, Richard Colvin Affidavit to the Military Police Complaints Commission, 2009.[19]

- Morris Davis, Former Chief Prosecutor for the Terrorism Trials at Guantanamo Bay, ‘Petition: President Obama: Close Detention Facility at Guantanamo Bay’, 2013.[20]

With these at hand, do you think ‘all persons are equal under the law’? Is there a difference between Jal, Beah, the ‘Lost Boys of Sudan,’ and Khadr? Let’s assume they are all child soldiers, based on the facts of their cases, do you think like cases were treated alike, or discretion and arbitrariness smeared the law of rules?

[1] Concluding Observations on the combined third and fourth periodic report of Canada, adopted by the Committee at its sixty-first session (17 September – 5 October 2020), paras 77-78.

[2] Megan Mylan and Jon Shenk, ‘The Lost Boys of Sudan’ (2004) Actual Films, 87mins

[3] Christain Karim Chrobog, ‘Emmanuel Jal: War Child’ (2008) Syndicado,1hr 32mins

[4] UNICEF, State of the World’s Children: Children in War (1996) available athttp://www.unicef.org/sowc96/closboys.htm

[5] Sara L. McKinnon, ‘Unsettling Resettlement: Problematizing the ‘Lost Boys of Sudan’ Resettlement and Identity’ (2008) 72 Western Journal of Communication 4 at 397-414

[6] Also see Ismael Beah Foundation available at http://www.beahfound.org and Beah’s interview on The Hour with George Stroumboulopoulos available at:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5K4yhPSQEzo

[7] See Soapbox: Former Child Soldier Michael Chikwanine, available athttp://www.cbc.ca/strombo/social-issues/soapbox-former-child-soldier-michel-chikwanine.html or http://www.law.utoronto.ca/faculty-staff/full-time-faculty/audrey-macklin

[8] Janice Williamson, Omar Khadr: Oh Canada (Montreal, QC: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2012) at xv. See also Audrey Macklin’s ‘Khadr’s Case Resource Page’, Bora Laskin Library, University of Toronto Law School, available at http://library.law.utoronto.ca/khadr-case-resources-page

[9] ‘Free Omar Khadr’ campaign website: http://freeomarakhadr.com/about/ . See also: OC-1 CITF witness report, 17 March 2004, in ‘Omar Khadr: The continuing scandal of illegal detention and torture in Gauntanomo Bay’, Fara McLaren, Lawyers Rights Watch Canada, June 2008, available at: http://www.lrwc.org/ws/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/Omar.Ahmed_.Khadr_.Fact_.Summary.June_.1.08.pdf

[10] Affidavit of Omar Khadr, 22 Feb 2008. See also ‘The US vs Omar Khadr’, a Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Documentary available athttp://www.cbc.ca/documentaries/doczone/2008/omarkadr/ and Canadian Security Intelligence Service – 2003 Interviews with Omar Khadr – Media Coverage, available athttps://www.csis.gc.ca/nwsrm/nwsrlss/prss20080721-eng.asp

[11] Canada (Prime minister) v. Khadr, 2009 FCA 246 (2009)

[12] U.S. Department of Defense, ‘Details of Omar Khadr Plea Agreement Released’ (31 October 2020) available at http://www.defense.gov/releases/release.aspx?releaseid=14024

[13] See, Canadian TV ‘Toews stands firm: Omar Khadr is a terrorist, not a child soldier’ (21 October 2020) available at http://www.ctvnews.ca/politics/toews-stands-firm-omar-khadr-is-a-terrorist-not-a-child-soldier-1.1004300#ixzz2XsRZjh59

[14] Andy Worthington, The Guantanamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (London: Pluto Press, 2007) at 185-187.

[15] See, The Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children in Armed Conflict, Press Release (10 August 2020), available athttp://childrenandarmedconflict.un.org/press-releases/10Aug10/

[16] Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada, ‘Children and armed conflict’ (30 April 2020) available at http://www.international.gc.ca/rights-droits/child_soldiers-enfants_soldats.aspx

[17] Clyde H. Farnsworth, ‘The killing of a Somali Jars Canada’ (11 February 2021), available at http://www.nytimes.com/1996/02/11/world/the-killing-of-a-somali-jars-canada.html

[18] Texas Citizens for Science, ‘The Bush Administration Torture Memo Scandal’, available at http://texscience.org/reform/torture/

[19] The Parliament of Canada, 40th Parliament, 2nd Session: Special Committee on the Canadian Mission in Afghanistan, (18 November 2020), available athttp://www.parl.gc.ca/HousePublications/Publication.aspx?DocId=4236267&Language=E#Int-2955390

[20] National Public Radio, ‘Why former Gitmo Chief left in protest’, (24 May 2020), available at http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=186440800

source: REGARDING RIGHTS Academic and activist perspectives on human rights