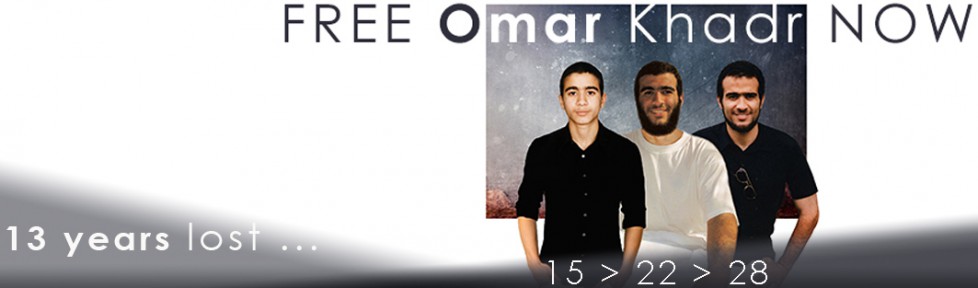

The International Child Soldier Standards in the Case of Omar Khadr

12 years unlawfully detained since age 15

Omar Khadr was a minor when he allegedly committed the acts that form the basis of the charges against him. Both US and international law require governments to provide children (persons under the age of 18) with special safeguards and care, including legal protections appropriate to their age. While children should be held accountable for their crimes, international law requires that they be treated in a manner that takes into account their particular vulnerability and relative culpability as children, and focuses primarily on rehabilitation and reintegration.

A body of international treaty law and standards establish fundamental norms when dealing with alleged juvenile offenders. The main sources are the following:

• International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)

• Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC)

• UN Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of their Liberty (UN Rules for the Protection of Juveniles)

• UN Guidelines for the Prevention of Juvenile Delinquency (The Riyadh Guidelines)

• UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice (Beijing Rules)

• Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (Standard Minimum Rules)

• Body of Principles for the Protection of All Persons under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment (Body of Principles).

The United States has consistently failed to uphold these internationally accepted standards in the case of Omar Khadr. Specifically:

1) Length of detention/prompt determination of case: International standards provide that the arrest and detention of a child must be used only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time, and that the case be handled as “speedily as possible.” (ICCPR 10. 2(b), CRC art. 37(b), 40(2)(b)(iii); UN Rules 2.)

Khadr was detained at Guantanamo for more than three years before he was charged in January 2006 under the first set of military commissions set up by President George W. Bush. His case was dismissed when the Supreme Court declared those commissions unlawful in the case of Hamdan v Rumsfeld in June 2006.

2) Legal Assistance: Every child deprived of his or her liberty is entitled to prompt access to legal and other appropriate assistance. (CRC art. 37(d), 40(2)(b)(ii))

Omar Khadr was not provided access to legal counsel until November 2004, more than two years after he was first transferred to Guantanamo.

3) Separation from adults: International law provides that every child deprived of his or her liberty shall be separated from adults, with the exception of unusual cases in which it is not in the child’s best interest to maintain such separation. (ICCPR 10, 2, CRC art. 37(c))

Khadr has been detained with the general detainee population at Guantanamo since he was 16. In 2003, the US government took steps to segregate other child detainees (three children estimated to be between the ages of 13 and 15) from the adult population in a separate facility, but refused to take such action in the case of Khadr, despite his status as a minor.

4) Contact with family: Detained children have the right to maintain contact with their family through correspondence and visits. (CRC art. 37(c)).

In five years of detention, Khadr has been allowed to speak to his family by telephone only once. His family has never been allowed to visit him.

5) Education, recreation: Children deprived of their liberty have the right to special care and assistance, including the right to education and recreation.(Beijing Rules 13.5, UN Rules for the Protection of Juveniles 12, 18(b)(c), 38, 47.)

Although US authorities provided other children held at Guantanamo with access to specialized tutors, a designated social worker, and recreational opportunities, these options were not made available to Khadr.

6) Specialized juvenile justice systems and rehabilitation: Child offenders should have access to specialized juvenile justice systems, with specially-trained judges, prosecutors and attorneys. A cornerstone of international juvenile justice standards is also a focus on rehabilitation and social reintegration. (ICCPR 14 (4), CRC art.40(1), Beijing Rules 2.3.)

Khadr has never had the opportunity to request that his case be transferred to a specialized juvenile justice system or the consideration of a non-judicial disposition. He has not been afforded access to specially-trained judges or prosecutors with expertise in juvenile justice standards or the particular needs and rights of alleged juvenile offenders. No consideration has been given to his rehabilitation or eventual reintegration into society.

No international criminal tribunal established under the laws of war, from Nuremberg forward, has prosecuted a former child soldier for violating the laws of war. There is an overriding presumption in international law that any exception be expressly authorized. The Special Court for Sierra Leone (“SCSL”) is one such exceptional case and its jurisdiction was limited to promoting the child’s “rehabilitation, reintegration into and assumption of a constructive role in society.” Even with these qualifications, the SCSL has made it its policy not to prosecute any former child soldiers.

In 2000, the United States signed the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict and ratified it in December 2002. Article 6(3) of the Optional Protocol obliged States Parties to take all feasible measures to ensure that persons within their jurisdiction recruited or used in hostilities contrary to the present protocol are demobilized or otherwise released from service. States Parties shall, when necessary, accord to such persons all appropriate assistance for their physical and psychological recovery and their social reintegration.

The rehabilitation of former child soldiers generally entails reunification with the child’s family, counseling, educational and vocational training, and other necessary assistance to aid their reintegration into society. The “Paris Principles,” international guidelines regarding children associated with armed forces or groups state that “at all stages,” the objective of programming for children who have been involved with armed forces should be to enable children “to play an active role as a civilian member of society, integrated into the community and, where possible, reconciled with her/his family.”

The Principles further state that regardless of whether children who have participated in armed forces or armed groups escape, are abandoned, or are captured by opposing forces, “all appropriate measures to promote physical and psychological recovery and social reintegration must be taken.”

In late 2003, the United States released three children (ages 13-15) detained at Guantanamo to UNICEF to enable them to receive rehabilitation and reintegration assistance in Afghanistan. However, the United States government has not made any such rehabilitation assistance available to Omar Khadr, nor acknowledged his possible status as a child used in armed conflict.

.

source | www.law.utoronto.ca/documents/Mackin/Khadr_ChildSoldier