by Steven Edwards | 24 May 2010

NEW YORK — Officials in the Obama administration demanded a game-changing rule change for the Guantanamo Bay military tribunal that would have likely scuttled the war crimes murder charge against Canadian-born terror suspect Omar Khadr, Canwest News Service has learned.

The officials sought to strip a new commissions manual of a law-of-war murder definition that is central to Mr. Khadr’s prosecution in the mortal wounding of Special Forces Sgt. First Class Chris Speer during a 2002 firefight in Afghanistan, insiders say.

Omission of the segment could have also obliged prosecutors to trim or abandon “up to one-third” of its cases, according to one inside estimate. Prosecutors said in the wake of the Bush administration they were prepared to take about 60 Guantanamo detainees to trial — among them the accused co-conspirators of the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks.

The Pentagon issued its 281-page Manual for Military Commissions on the eve of hearings April 28 to May 6 in the Khadr case after the U.S. Congress updated the Bush-era Military Commissions Act with legislation President Barack Obama said makes them fair. Prosecution and defence teams use the courtroom rules to present their cases, but a new manual was necessary to conform to the legislative changes in the 2009 act.

The failed bid to change part of law-of-war murder rule — as well as separate arguments insiders say took place over other rules — illustrates how the commissions remain a point of division in the Obama administration. Numerous appointees — and even Mr. Obama himself — were sharply critical of the tribunals after the Bush administration launched them as a key tool in its post-9/11 “war on terror.”

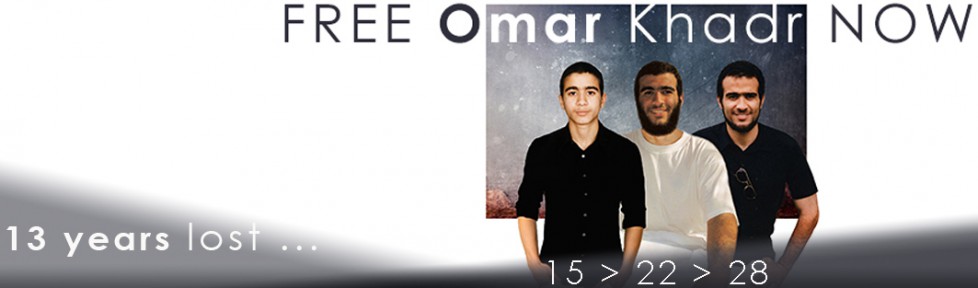

The government infighting also took place against a backdrop in which some in the Obama administration are uneasy about proceeding towards Mr. Khadr’s scheduled Aug. 10 trial given he was 15 at the time of his capture following the 2002 firefight.

Among those leading the charge against the contested murder segment was Harold Koh, Obama-nominated legal adviser of the State Department, who once wrote that the U.S. was part of an “axis of disobedience” along with North Korea and Saddam Hussein’s Iraq.

Also involved in seeking an edit were people in the U.S. Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel, insiders add. OLC, which assists U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder in advising the president, employed two lawyers of a group the politically conservative campaign Keep America Safe recently dubbed the “al-Qaida Seven” because they had worked on behalf of terrorism suspects.

One of the two, Karl Thompson, did work for the Khadr defence team for seven months from October 2008 while he worked for the firm O’Melveny &Myers, Fox News reported in March.

The pretext for demanding the draft-rule edit centred on concern about defending the legitimacy of Central Intelligence Agency drone attacks on terror suspects in Pakistan, one insider confided.

According to this official, it was feared that aspects of the commission manual’s “comment” in the section titled Murder in Violation of the Law of War could be applied to the attacks. Key among the contested phrasing is a statement that says murder and some other offences rise to the level of war crimes if committed “while the accused did not meet the requirements of privileged belligerency” — which principally covers regular war law-abiding combatants.

But once the purported concern got raised “up a level,” as the source put it, it appeared to be quickly dropped — leading some on the Pentagon side to believe that motives aimed at weakening the commission structure as a whole may have been at play.

Mr. Koh surprised conservatives in late March with a major speech in which he asserted the U.S. right to use unmanned drones to kill terror suspects overseas — on or off the battlefield.

But insiders say he made clear in internal U.S. government deliberations on the commissions manual that he considered “inappropriate” some of the key phrasing in the “comment” on the war crimes murder charge.

U.S. Defence Secretary Robert Gates signed off on the manual with the contested “comment” intact after Jeh Johnson, his legal adviser, went head-to-head with Koh, one official recounted.

“Harold Koh doesn’t have any authority over the defence department,” said this official. “The general counsel of DOD was fighting Koh on it; he advises Secretary Gates . . . who is going to follow his own lawyer.”

Within the Obama administration, Mr. Koh is perhaps the “most sensitive” to the question of whether Mr. Khadr, now 23, should be considered to have been a “child soldier” who needs rehabilitation, not prosecution, according to one person intimately knowledgeable about the Khadr case.

Mr. Koh was dean of Yale Law School in 2007 when Mr. Khadr’s defence team, then led by U.S. navy Lt. Cmdr. Bill Kuebler, conducted a “clinic” at the institution in which Yale students did legal research in the case.

Mr. Khadr’s current U.S. lawyers — led by civilian Barry Coburn, but including Pentagon-appointed army Lt. Col. Jon Jackson — may try to revisit the controversy either before or during his trial in a bid to have the military judge strike the phrasing.

Analysts say they could argue it strays from the wording Congress initially approved in the updating 2009 legislation, while prosecutors would counter that it accurately reflects the Congressional intent.

The defence has had some past success making such an argument: In 2008, Mr. Khadr’s team under Lt. Cmdr. Kuebler managed to get wording in a conspiracy charge pared down after arguing that the defence secretary lacked legislative authority to expand on the definition of the charge. Still, the overall charge that Mr. Khadr “conspired and agreed” to commit terrorist acts remains.

Mr. Khadr faces up to life imprisonment if convicted of all five war crimes charges filed against him. The military judge is expected to rule in the coming weeks whether the prosecution can at trial use self-incriminating statements Mr. Khadr made during interrogations, as well as other evidence.

While the defence argued during the recent hearings that Mr. Khadr had faced torture and coercion ahead of making the statements, prosecutors sought to show he had spoken voluntarily.