By Aisha Maniar | August 31, 2020

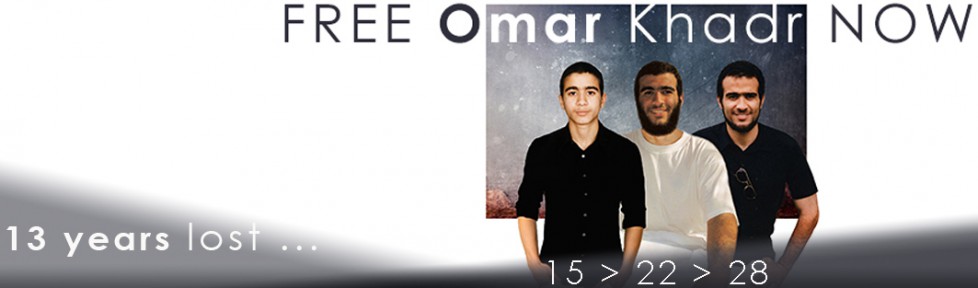

Omar Khadr’s appeal case against his conviction by a Guantánamo Bay military commission has been the subject of court action in the U.S., both directly and indirectly, in recent weeks.

In the first instance, a redacted memo by the U.S. Office of Legal Counsel (OLC), released in June under a Freedom of Information order and dated shortly before Omar Khadr’s 2010 military commission hearing, shows that the U.S. deliberately designated Khadr an “unprivileged belligerent”. This enabled the U.S. to charge him with offences it knew did not exist under domestic or international law and to deny him protection under the Geneva Conventions.

(Gail Davidson of Lawyers’ Rights Watch Canada reported on the bogus nature of the charges against Omar Khadr in detail here.)

Following this revelation, on 30 June 2014, Khadr’s legal counsel in the U.S. filed a motion with the U.S. Court of Military Commission Review (CMCR) to have the stay on Khadr’s case lifted and his conviction quashed on the basis that “the disclosure of a previously secret memorandum […] which provided authoritative legal guidance to the Department of Defense several months prior to Mr. Khadr’s guilty plea, invalidates the theory of criminality underlying this prosecution and therefore defeats the premise of the Court’s order.” The motion sets out that the memo made it clear to the U.S. authorities that there was no legal basis for the case against Omar Khadr and that the U.S. was fully aware of this.

On 7 July, counsel for the U.S. government filed a motion asking the court to deny the motion filed by Khadr’s lawyers “because there has been no change in the underlying basis” of the court’s original stay of the case in March 2014 and because the memo is “irrelevant” to Khadr’s case. However, the CMCR denied Khadr’s motion before his lawyers had an opportunity to respond. Khadr’s U.S. lawyer Sam Morison called this response predictable. As a result, according to Morison, “the issue is not going away any time soon”. Indeed.

Four months earlier, in March 2014, Khadr’s case (and that of Australian former prisoner David Hicks) was stayed by the CMCR pending a judgment in an appeal by another Guantánamo prisoner, Ali Hamza Al-Bahlul from Yemen. Bahlul had been given a life sentence in 2008 for conspiracy, providing material support for terrorism, and soliciting others to commit war crimes. Following the successful appeal by fellow Yemeni Salim Hamdan in 2012, in which Hamdan’s conviction was quashed on the basis that his offence, providing material support for terrorism, “did not constitute a war crime,” Bahlul saw his three convictions quashed in January 2013, but the U.S. government was granted a retrial en banc (whereby all the judges in the appeal court make a ruling). The judgment in this long-awaited appeal was handed down on 14 July 2014. It essentially ruled to “reject Bahlul’s ex post facto challenge to his conspiracy conviction and remand that conviction to the original panel of this Court for it to dispose of several remaining issues. In addition, we vacate his material support and solicitation convictions.”

Bahlul’s case has a knock-on effect on pending and future military commissions as well as on other appeals, such as those of Khadr and Hicks. The en banc rehearing was largely admitted on the basis that, while the U.S. government conceded that the quashed convictions of Hamdan (this ruling was also reconsidered by the seven-judge panel) and Bahlul were not recognized under the international laws of war prior to 2006, when the Military Commissions Act 2006 came into force, they were recognized under the “U.S. common law of war.” On this basis, the court quashed two of Bahlul’s convictions (material support and solicitation of others to commit war crimes), finding that the government did not provide historical evidence so that such charges could be upheld in a U.S. domestic context. But, the court decided that there was sufficient precedent in the case of conspiracy and, hence, this conviction was upheld.

Nonetheless, that does not settle this key issue or the other key point of the rehearing – whether the U.S. common law of war can provide a basis for these alleged war crimes – as the court then sent the conspiracy issue back to the three-judge panel, who heard the original appeal, to consider arguments. This granted them the possibility of overturning this ruling before the entire case is returned to the CMCR to assess the effect of the judgment on Bahlul’s life sentence. Essentially, in a confusing 150-page sentence, the court failed to settle the key questions put to it, and its judgment paves the way to further arguments and appeals.

The 4–3 decision by the seven-judge panel overhauled a major aspect of the Hamdan ruling by deeming that the Military Commissions Act 2006 can have retroactive effect. Thus it can be used to charge and try crimes committed prior to it – as it claims that the Act is unambiguously intended to try any offence punishable by it committed “before, on, or after September 11, 2001” and to prosecute individuals allegedly involved in the 9/11 attacks that took place in 2001. In spite of this, the court dismissed Bahlul’s claim on his ex post facto conspiracy conviction, finding that engaging in a conspiracy to kill a national of the United States is already criminalized under the U.S. Constitution and that a precedent for this already exists in U.S. case law.

While the court clearly established that material support and solicitation are not war crimes under international or domestic law, the decision on conspiracy is couched in such vague terms that it is not clear how it will apply to other prisoners, including Omar Khadr, who was also convicted of this charge under his secret plea bargain. Al-Bahlul’s lawyers now have the option of appealing to the U.S. Supreme Court or waiting to see what the original panel has to say on the outstanding matters. In either case, nothing will be settled before next year.

The decision was always going to be complicated and highly politicized, with the largest ramifications for Al-Bahlul himself, who even if cleared, may remain held in limbo at Guantánamo. The impact on other cases is also unclear. In Hicks’s case, the judgment should mean that his sole conviction of material support for terrorism is now quashed; his Australian lawyer has stated that overturning the conviction should now be “a purely administrative matter.” The U.S. Centre for Constitutional Rights announced that it will assist David Hicks in filing of the motion to get his Guantanamo conviction overruled.

For Omar Khadr, the implications are vaguer and indirect. While his conspiracy conviction is affected, the U.S. government has nonetheless conceded, “Khadr did not violate either a pre-existing statute or the international law of war.” Both Khadr and Hicks may have to await the final outcome in Al-Bahlul’s case, which could take years, in order for the CMCR to progress with their own appeals. The waiting game continues.

The only two things that can be concluded are that the web of deceit spun by the use of military commissions and their extralegal devices can only become further tangled, and that the procedure itself is designed only to waste the time of prisoners who the U.S. knows in many cases to be innocent of the charges against them. Responding to the judgment, the Center for Constitutional Rights, stated: “The court merely deferred the inevitable by failing to recognize that conspiracy is no more appropriately tried in a military commission than material support. We urge the Supreme Court to review today’s ruling regarding conspiracy and dispense with all fabricated war crimes charges once and for all.”

Aisha Maniar is a human rights activist who works with the London Guantánamo Campaign.

The London Guantánamo Campaign has been campaigning since 2006 for the release of all prisoners held at Guantánamo Bay, the closure of Guantánamo and other similar prisons and an end to the practice of extraordinary rendition.

.