By Aisha Maniar | June 3, 2020

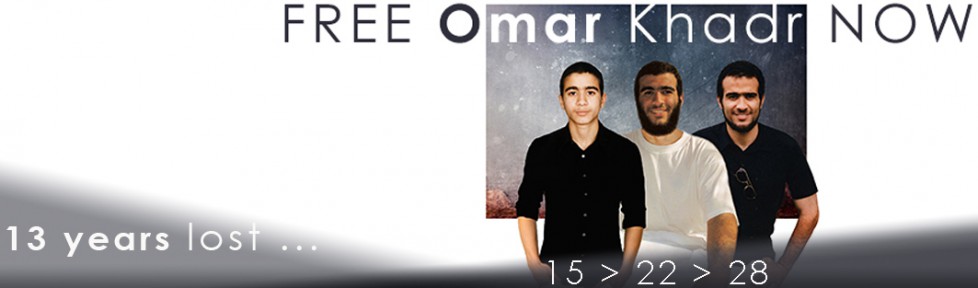

In 2004, Scottish-Canadian criminal defence barrister Dennis Edney QC was asked to provide legal representation to Omar Khadr, a Canadian citizen seized by the US military in Afghanistan in 2002 aged just 15. Having suffered serious injuries in the gun battle in which he was captured, Khadr was then tortured at Bagram Airbase in Afghanistan before being taken to Guantánamo, where he was held until September 2012.

In 2010, in a move condemned internationally, Khadr became the only person since World War II to be tried, and later convicted in a secret plea deal, as an adult for war crimes allegedly committed as a minor. Edney represented Khadr during his military tribunal at Guantánamo and in successful cases before the Canadian courts to vindicate his human rights. Under pressure from the US military, Khadr later fired Edney and his co-counsel Nate Whitling.

Upon release to Canada in late 2012, where he remains incarcerated to date as he serves the remainder of his Guantánamo military tribunal sentence, Khadr later reappointed Edney, who is currently representing him in several court cases before the Canadian courts and an appeal of his Guantánamo conviction in the US courts.

Omar Khadr remains almost unknown outside of Canada, yet is vilified by the media and politicians within. During a visit to the UK, on 17 March 2014, I put some questions to Dennis Edney QC about his extraordinary client.

1 – It’s been a decade since you first represented Omar Khadr at Guantánamo Bay. What was your view of the prisoners and of the legal regime there before that? What did you think you were getting yourself into?

It has been well over a decade since I first visited Omar Khadr in Guantánamo Bay. When I first arrived there, I understood intellectually that it was a place beyond the rule of law, but there was nothing in my experience like Guantánamo Bay, nothing to prepare me for the place. I was an everyday trial lawyer who goes to court, then goes back to his office to take on another client. At the end of the day, I go home to the comfort and love of my wife and children and I get on with life, and then it hit home that there was such an evil place as Guantánamo, an American gulag. It was a shock to my system, and I had no idea of what I was getting into, not the slightest. I’ve said many times that when I got off the plane in Guantánamo I felt that I was a bit special, because I was one of the few people who actually got into Guantánamo, but I recall when I left Guantánamo that first time and checked into a hotel in Jacksonville, Florida, I found myself quietly weeping. My whole self was trying to adjust to the experience of Guantánamo.

2 – Having experienced the “legal” regime at Guantánamo Bay and military commissions, how would you describe them to someone who’s been comatose for the past 12 years?

I can simply say that it is a place beyond the rule of law; it’s an evil place. As long as we allow places like Guantánamo to exist, the very nature of who we are comes into question. None of us are safe when we allow places that are beyond the rule of law, specifically set up to avoid oversight, and there specifically to torture people to get information.

The use of the word “legal regime” in your question itself is somewhat confusing, as first of all there is not a properly constituted court of law. It’s not a place where there is such a thing as due process. It is there just to provide cover for the administration; it’s there to find people guilty. It’s not there to balance the facts and make a fair decision.

Omar Khadr is a point in question. Torture memos were not allowed to be used in his trial. People who could give evidence about his torture and abuse at Guantánamo were not allowed to be called as witnesses. Omar Khadr was not allowed to use the defence of self-defence and overwhelmingly, the amount of disclosure that was necessary to give him a fair trial was not allowed in. I could go on and on.

The judge was specifically picked by the Pentagon. You had handpicked jurors, there to give the right decision. The military defence counsel imposed upon Omar either had limited trial experience or none at all. I came to the conclusion that they were either incompetent or simply reckless with no sense of understanding of what was involved in representing a client. It’s all about smoke and mirrors at Guantánamo.

3 – Outside of Canada, Omar Khadr is little known. Yet, in Canada, politicians and journalists who’ve never met him describe him as being “controversial” and “polarising”. Having met him yourself and having agreed to represent him, what can you tell us about Omar Khadr, the person?

It’s an important question and it is important to repeat that nobody in the media has ever met Omar Khadr or interviewed Omar Khadr. The problem is that he has never been permitted, whether in Guantánamo or in Canada, to speak to the media to challenge the assertions made about him. I will be in court over the next few months challenging the Canadian government’s media injunction.

For me, it’s a privilege to represent Omar. I learn from him. I admire him. There are times when I look at him that I have to remind myself of all the horrors that he has been through, and yet he has retained his humanity and his compassion. He is full of excitement about getting on with life and he is rabid about learning. He wants to make up for lost time. When I ask him, what is it you want to do when you grow up? – not that he’s not grown up now – he says he wishes to be a doctor, and when I ask him why, he says because I never want people to be abused like me. Omar has no bitterness; he has nothing but forgiveness. He would be such a contribution to Canadian society.

4 – When Omar Khadr returned to Canada in September 2012, he had a different counsel. You resumed his representation a few months after he returned. Given the hostility Khadr faces in Canada, what made you decide to take on his case again?

The background to my firing is important to answer your question. I had gone to Guantánamo Bay after the trial, to visit Omar and determine whether the information we were receiving was correct, that he was back in one of the secret prisons and being subject to prolonged interrogation sessions. During my visit, Omar had mentioned to me that he was being interrogated nine hours a day for nine-day periods by two separate groups. He also said that our military defence lawyers knew about this and allowed it.

I confronted one of the military lawyers and told him I had been invited to speak to the American Bar, which involves maybe a thousand lawyers, and I would be talking about not only their incompetence at trial, but the fact that they allowed our client to continue to be abused after trial. As a result of that, they spoke to Omar and pressurised him into signing a document that they typed out terminating me and my co-counsel Nate Whitling. I was also banned from visiting him in Guantánamo. I was angry, but chose to move on. In some way, it was a relief to escape the everyday fighting for Omar.

On Omar’s return to Canada, he requested me to visit him. I happened to be flying into Toronto from Argentina and went to visit him in the Milhaven maximum security prison. It was lovely to see him, and he was delighted to see me. I was reminded of my promise to him when he was a child that “I would never leave him”.

Do I regret coming back? Not at all, because he is worthy of all the help I can give. I don’t resile from the fact that Omar represents goodness. I’ve said that to people many times. Omar is special. I think it is a great gift to work to return him whole to society. He’s been a great gift to me; he and his Guantánamo detainees have helped me be a more human person.

5 – How politically-motivated is the legal treatment of Omar Khadr in Canada, both with respect to the Canadian and US governments?

The whole case is politically motivated. Guantánamo and the war on terror is an overstated theme. We have a government, who when criticised by the Canadian Supreme Court for participating in the torture of a young Canadian boy, a citizen, showed no remorse, said nothing, and we the Canadian public didn’t seem to be bothered that the Supreme Court was saying that your own government was participating in the torture of one of our most vulnerable, a child. This government can get away with it so long as the apathy of Canadians remains.

6 – Omar Khadr currently has a couple of cases going through the Canadian courts and is appealing his US conviction. What can you say about those cases and where they are heading?

My co-counsel Nate Whitling and I have been successful in the US Supreme Court once and twice in the Canadian Supreme Court. It hasn’t been based upon traditional common law. We have expanded the constitution extraterritorially. We have been in every court of the land over the years, and have fought in three international jurisdictions on behalf of Omar – the US, Canada and Guantánamo Bay. It’s no different today.

Next month, I’m in the Alberta Court of Appeal*, asking that Omar Khadr be released from a federal prison because he’s a juvenile. I anticipate that there is a very good chance that I’ll be successful. The problem is that this government has never allowed me to rest on my laurels and will probably take me to the Supreme Court of Canada.

While I’m hoping that will work, I’m also challenging his security classification. I’m relying on a report from the Canada ombudsmen, reports from the institutions themselves and reports from abroad, particularly a report by the Undersecretary of State for the United States which says that Omar poses no problem to anybody. He has no radical and ideological thoughts that one should be concerned about. The whole purpose of that application, which is before the federal courts, is that it will get him out of jail quicker. I also have an ongoing civil lawsuit against the Canadian and US governments for conspiring to keep Omar in Guantánamo Bay.

I recently filed a joint brief with Sam Morrison, a military lay lawyer and I anticipate that case will go to the Supreme Court in the United States, because we’re attempting to overturn Omar’s charges. It is not hard to understand that the charges are not known in international law. These are nullities that I hope the court agrees with. I’m following Hamdan, who was successful with similar arguments. My difficulty is that I have to start off at the military commission level and then work right through the federal court system.

You need look no further than at Guantánamo Bay, which continues to exist, to understand how easy it is to fall into lawlessness, but we are only able to define the boundaries of permissible and legitimate state action by making governments adhere to the rule of law.

On the same day, as part of a speaking tour I organised with the London Guantánamo Campaign, Dennis Edney QC spoke at a public meeting with former British servicemen from Veterans for Peace UK, some of whom had served in Afghanistan at the same time and on the same side as the US servicemen Omar Khadr is alleged to have killed and injured:

* This appeal took place on 30 April and the judgment is pending.

.

Aisha Maniar runs the London Guantanamo Campaign. She interviewed Dennis Edney QC during his UK speaking tour to raise awareness for his client Omar Khadr. The UK speaking tour was organized by London Guantanamo Campaign and the Free Omar Khadr Now Campaign. Dennis Edney tells about the upcoming court cases (including the appeal to overrule Omar’s illegitimate Guantanamo conviction), the unacceptable government interference and Omar’s admirable personality.

The article is originally published on On a Small Window…

Image courtesy of Richard K. Wolff

.