By Aisha Maniar | Februari 25, 2013

Omar Khadr, the youngest prisoner at Guantánamo Bay was released to Canada on 29 September 2012, ten days after his 26th birthday. Captured in Afghanistan in July 2002 aged 15, his release should have been good news, ending a journey that started halfway across the world and has seen him spend almost half his life behinds bars. Instead, upon return, he was taken immediately to the Millhaven Institution in Bath, Ontario, a maximum security prison, where he remains imprisoned.

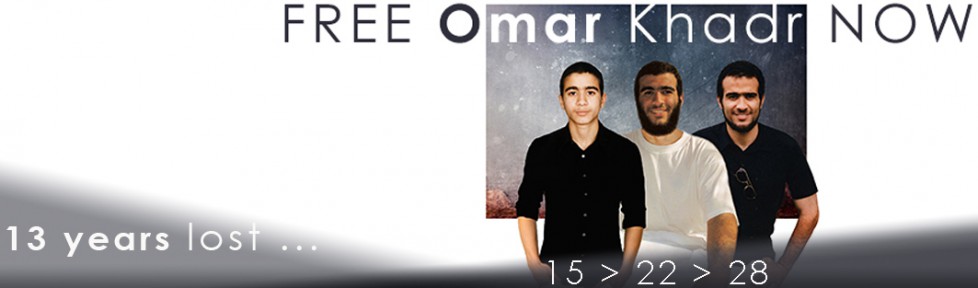

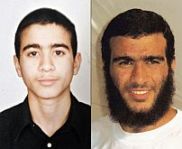

Omar Khadr in 2002 and 2010

Each of the almost 800 prisoners held at Guantánamo has a compelling tale to tell, yet Omar Khadr’s is unique in many ways: the most obvious distinction being his age. Unlike other child prisoners, he was always treated as an adult. Subject to torture, including waterboarding, this provided some of the evidence used to charge him for various war crimes shortly after he turned 19 in 2005.

Omar Khadr’s military commission has unique features: upon inauguration to his first term as president, constitutional lawyer Barack Obama signed a presidential decree to close Guantánamo and suspend military commissions. Neither has happened and with a revised Military Commissions Act in force by the end of 2009, Khadr was the first person to be tried in Barack Obama’s presidency. As the offences he is alleged to have committed took place when he was 15, he is also the only person to be tried by a military tribunal for war crimes committed as a minor since World War II. This disturbing development received international condemnation.

Facing a life sentence without proper due process, in a secret plea bargain in October 2010, he pleaded guilty to all the charges against him: the murder of an American soldier, attempted murder, conspiracy, material support for terrorism and spying. Possibly his only way out, under this deal, he would serve just one more year at Guantánamo Bay and the remaining seven years of his sentence in Canada. Although not a party to the bargain, the exchange of diplomatic notes to the effect that Canada would agree to repatriate him after an additional year in Guantánamo was a part of this agreement. Omar Khadr was due for release in October 2011; it took another 11 months for it to happen.

This is largely down to the Canadian government. Having only met all of Canada’s conditions for repatriation in April 2012, the US then formally submitted Omar Khadr’s transfer application. Vic Toews, the Canadian Minister of Public Safety, responsible for this transfer, sought medical reports and a video to help make his assessment of the security risk he posed. This video was an interview conducted with Omar Khadr by Dr Michael Welner, a psychiatrist and prosecution witness who described him as “highly dangerous” and having “rock star” status at Guantánamo. Influential during the trial, Welner’s evidence is known to be biased and has been discredited by other psychiatrists. Writing in the New York Times shortly after Khadr’s release, Dr Stephen N. Xenakis, a retired psychiatrist and former US army brigadier general, who had spent hundreds of hours assessing Khadr since 2008, stated that he was “emphatically not” the dangerous man Welner claimed.

In his own psychiatric report to Vic Toews, submitted in February 2011, Xenakis dismissed Welner’s findings and approach: “He based his opinion on clinical interviews and reviews of medical records from his capture and detention. His findings are questionable as his medical examination did not follow the standards of usual practice.” Xenakis’ own assessment is that “Mr. Khadr can successfully transition from Guantanamo because of his remarkably positive outlook, his talent for building positive relationships, and his optimistic temperament.” He further advised that “keeping him incarcerated and living under conditions of imprisonment provides little chance for rehabilitation or preparation to live in society.” This report was ignored.

Legal formalities and posturing aside, Canada could have demanded Omar Khadr’s return at any time. Indeed, this request for information was further stalling of the repatriation; having received the information in early September, Vic Toews’ request was accepted days after it was sent. Canada could have requested his return to the country at any time since July 2002. Omar Khadr stands out as the only western citizen whose country did not seek his repatriation.

Canada’s treatment of Omar Khadr has smacked of hypocrisy and duplicity throughout: a champion of the rights of war children, Canada was an early signatory of the Optional Protection of the International Convention on the Rights of the Child (ICRC) on the involvement of children in armed conflict in 2000. In 2008, a report by the Canadian House of Commons Subcommittee on International Human Rights recommended the Canadian government seeks Khadr’s immediate release and that “an appropriate rehabilitation and reintegration program is developed for Omar Khadr.” Also in 2008, it emerged that Canadian intelligence officers had interrogated him at Guantánamo in 2003 in a process that breached international law. The Canadian Supreme Court ruled in 2010 that the Canadian government’s refusal to repatriate him was unconstitutional and breached his rights under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, but stopped short of ordering it to demand his release. As recently as October 2012, in its review of children’s rights in Canada, the ICRC recommended that Canada rehabilitate Omar Khadr.

In making his safety assessment, Vic Toews chose to rely on Dr Welner’s prejudiced analysis. In astatement he made upon Omar Khadr’s return to Canada, Toews called Khadr “a known supporter of the Al-Qaeda terrorist network and a convicted terrorist”. Dr Welner’s untested allegations about the Khadr family’s association with terrorism and Omar Khadr’s alleged fundamentalist fervour saw him transferred immediately to “Millhaven, one of the toughest prisons in the country. [which has…] been dubbed “Guantanamo North”.” These elements were picked up immediately by the Canadian media, keen to paint Omar Khadr as unrepentant, an image that, while feeding media hysteria, also successfully deflected the Canadian government’s own negligence and betrayal of a Canadian citizen.

His situation is as precarious as it has been over the past decade, and his fate lies in the hands of Canadian justice, specifically the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC), which is overseen by Vic Toews. In late December, it emerged that the CSC considers Omar Khadr a “maximum security” prisoner due to his murder and terrorism conviction, with his status due to be reviewed in December 2014. This assessment fails to take into account the dubious conditions that, involving torture and an unfair legal process, helped to obtain this conviction and as a result, day parole which otherwise would have been due next month is now almost completely unlikely. Applying the “Custody Rating Scale” point system, his first-degree murder conviction confers him with enough points to be considered a “maximum security” risk. With Khadr back home, the Canadian government’s attitude does not seem to be changing. Recognising some of these longstanding issues, Amnesty Canada launched a campaign action last year, Omar Khadr: The Case is not closed.

One of the most unfortunate aspects of Omar Khadr’s ordeal is the Canadian government’s singular and dogged faith in the military commission system at Guantánamo Bay. During his military commission, the Canadian government was satisfied with US assurances about proceedings, particularly with respect to his age at the time being taken into consideration, in spite of international condemnation of both the US and Canada in this regard. Canada’s blind faith in the lawfulness of such convictions is one not even shared by the US’ own federal courts.

On 16 October 2012, the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit overturned the 2008 conviction of former prisoner Salim Hamdan by military commission for “material support for terrorism”, one of the charges Omar Khadr was also convicted of, due to the retroactive nature of the offence, as the alleged offences took place years before the Military Commissions Act created them. This crucial judgment made just weeks before the US presidential election shattered the illusion of any legitimacy the few convictions obtained at Guantánamo Bay may have. The US government had until January to appeal but did not. Last month, based on this judgment, another conviction, the life sentence of Yemeni prisoner Hamza Al Bahlul was also overturned. Omar Khadr is likely to appeal too. The Canadian government’s faith in the military commissions is undermined further by the ongoing farce of the 9/11 military commissions, also affected by the Hamdan ruling.

The onus is now on the Canadian government and questions over its failure to meet its legal and moral obligations to one vulnerable citizen. Beyond its mantra of “Omar Khadr is a convicted terrorist”, there is very little to sustain its untenable position.

Omar Khadr is not the only prisoner to have been further incarcerated on his release from Guantánamo Bay. Australian David Hicks, the first person to be convicted at Guantánamo Bay, entered a similar plea bargain where he pleaded guilty in return for a seven-year sentence, which was suspended except for 9 months which he served in an Australian jail. He was released in 2007. One day after the Hamdan judgment, he said he would appeal his conviction.

Guantánamo Bay has created its own “refugee” situation: of the remaining 166 prisoner, more than half are unable to return home. For many of the prisoners cleared for release, the option of going home does not exist for fear of further persecution and imprisonment. To deal with this “refugee” situation, various third states have accepted more than 40 prisoners. Slovakia agreed to resettle three such prisoners in a “”gesture of solidarity” in support of President Barack Obama’s foreign policy” in late 2009. However, by June 2010, six months after their arrival in Slovakia, the men went on hunger strike in protest at their continued detention at an asylum detention centre whose conditions they claimed were “worse than Guantánamo”. All three had been cleared for release years before arriving in Slovakia and were under the impression they would be resettled and rehabilitated. The situation improved following international awareness and criticism. After the Arab Spring in 2011, two of the men felt that the security situation in their home countries would be safe enough for them to return. Rafiq Al Hami returned to Tunisia where he is rebuilding his life with his family. Adel Al Gazzar, optimistic of the changes under the new regime in Egypt, was promptly arrested and imprisoned upon his return to the country in 2011 for a conviction made in his absence in 2002. He has since been released and reunited with his family. The third man, Polad Sirajov from Azerbaijan, remains in Slovakia.

Perhaps the worst case of post-return persecution is that of 29-year old Russian citizen Rasul Kudaev. From the Kabardino-Balkaria Republic (KBR) in the North Caucasus (southern Russia), he was arrested in Afghanistan aged 17* where he fled to avoid military service. Posing no risk, he was considered for transfer back to Russia by the US once the two countries had shared the intelligence beaten out of him at the end of 2002. He was released in February 2004. He returned home with a series of illnesses, a limp and physically unable to work. [Source: HRW].

Following militant attacks in October 2005 in the city of Nalchik where he lived, he was arrested with 58 others, and has been held since at a pre-trial detention centre where they are awaiting trial. Beaten as he was taken from his home, he had to be carried into court a few days later due to the severity of the beatings. By early November, pictures of his abuse and that of other prisoners circulated; Kudaev’s face was swollen and bruised. He was beaten so badly that human rights investigators fear he has permanent facial disfigurement. He was charged with various terrorism offences as a result. In 2006, his lawyers contested the evidence as it was obtained through torture but that was thrown out. His health has deteriorated progressively and his mother expressed serious concerns after a visit in January 2013.

The trial has been delayed for various reasons. The prosecution has given its evidence and Rasul Kudaev will be one of the last defendants to give his next month; the case should conclude later this year. His lawyers will also apply for bail until the judgment. In what has been largely a show trial, Amnesty International has expressed “little hope” in the outcome.

Years of abuse and injustice at Guantánamo Bay have so far resulted in a zero successful conviction rate and no credible evidence, just George Bush’s say-so that these are “bad men”. The least one may expect released prisoners to expect is rehabilitation and due process, and certainly not further imprisonment and persecution, especially of the most vulnerable. To deal with this pressing need,Reprieve, the human rights NGO which has and continues to represent dozen of prisoners, including the three men sent to Slovakia, set up the Life After Guantanamo project in 2010. Polly Rossdale from the project explains the needs former prisoners have and why such a project is so important:

“There has been no justice, apology, or compensation to a single victim of US-sponsored torture in Guantanamo. Former detainees are faced with the challenge of recovery from trauma in places and communities that are often either poorly resourced, lacking the necessary torture rehabilitation skills or are hostile to their presence. The Life after Guantanamo project seeks to facilitate appropriate medical, psychological, legal and social support for these men and their families. We assist with a range of issues including finding accommodation; family reunification; countering isolation; dealing with restrictions on freedom of movement and an uncertain legal status; and obtaining financial support to accessing education, training and employment.”

This year has seen some positive changes for Omar Khadr: last month, Dennis Edney, who previously acted as Khadr’s lawyer and championed his case far and wide, was reappointed to represent him in a case before the Canadian Federal Court against the Canadian government for breach of his constitutional rights. This move is likely to expedite his other demands and see the positive profile of his case rise again. Earlier this month, he was also moved out of solitary confinement, and is reported to be getting on well with other prisoners; this is the first time he has been out of solitary confinement since his conviction in 2010. A new petition has been put together calling on the Canadian government to release Omar Khadr and rehabilitate him, both a reasonable and the only viable proposition to deal with the current situation.

Many thanks to Reprieve and Amnesty International for their assistance. You can write to Omar Khadr at: Omar Khadr, Millhaven Institution, Hwy 33, PO Box 280, Bath, Ontario, K0H 1G0, Canada

* Rasul Kudaev was captured aged 17 (a minor) in Afghanistan, however by the time he arrived at Guantánamo in 2002 he was 18, a legal adult.

.

Source: http://onesmallwindow.wordpress.com/2013/02/25/omar-khadr-from-frying-pan-to-fire/

.