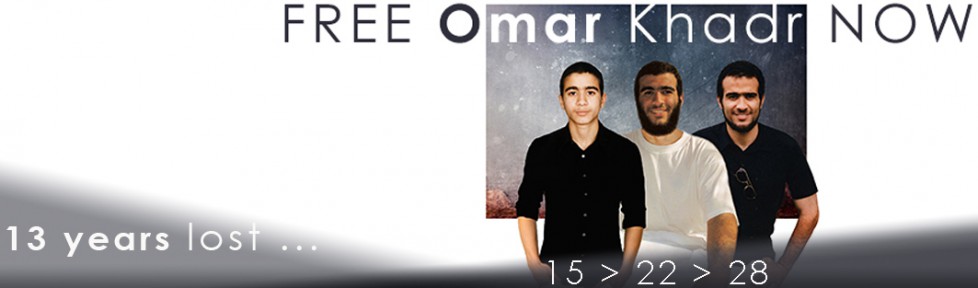

By Sara Naqwi - Free Omar Khadr Now

In helping edit this article, a personal note of deep gratitude to Marlene Cuthbert, who was passionate and completely devoted to seeing justice brought to her friend, Omar, until her last days.

Marlene passed away on March 25, 2015.

I was twenty-five years old when I first saw Omar Khadr’s young face, staring back at me through my laptop screen. The innocence in his big brown eyes combined with the sombre expression drew me in; the straight-backed posture which is typically alien on a teenager confirmed he was staring into the lens of a camera for a passport photo, perhaps being told by the cameraman to remain expressionless, yet the photograph still captured his cheerful disposition. There was a trace of a faint moustache on his baby face, with a hint of a smile in his eyes and mouth. This was a photograph of a young boy, who was barely fourteen years old.

I was completing my final year of Bachelors in English from a Canadian university and had decided to take a course, “Introduction to Law and Justice”, out of curiosity. One of the assignments I was asked to write about was on Omar Khadr’s case, and that is how I came to know about the young man who was to become an integral part of my life eventually. When I scanned the details of his case online, I was overwhelmed by the amount of heavy information revolving around this child. The words Guantanamo Bay, torture, war on terror, indefinite detention combined with the images of hooded men in orange jumpsuits, chained like animals and caged under the blazing sun in Cuba, where the prison is based, confounded me. I knew it was wrong – who wouldn’t be horrified by this abnormal treatment of human beings? – but I couldn’t fully appreciate the gravity of the situation. Even though I was aware of how Muslims had suddenly become targets of racism since 9/11, and news agencies like CNN and the BBC would constantly stream selective photos of bearded men and label them “terrorists”, I am ashamed to admit I knew little about the politics behind the war on terror. I didn’t know back then that you cannot label someone a terrorist until you prove his or her guilt in court. I didn’t fathom what methods were used by the US to capture these so-called terrorists. I knew absolutely nothing about the detainment and torture of women, children and the elderly in various CIA black sites. All I understood from the news and horror stories of families whose members were being targeted, is that the US was the most powerful nation on earth and because of 9/11, it was angry at the Muslim world and was seeking “revenge”. In October 2001, from the living-room in my home in Saudi Arabia, I was glued to the television for days as I witnessed the unforgettable images of the US invasion of Afghanistan, and beheld live images of the sweet Afghan children strewn across what was once their playground, lying dead, their families and homes levelled to the ground. Less than two years later, in May 2003, my friend Amal and I stayed up all night in her home in Lahore, as we caught live images of the bombardment that continued in Iraq. Through infra-red vision, the camera caught green eruptions against a black background with faint traces of cubes that indicated houses, shops and mosques. My thoughts were solely on the civilians, wondering, where are they hiding? Did they have basements they could take refuge in, the way most Americans do when a hurricane or tornado hits areas like Minnesota or Kansas? Incidentally, little did I know that Amal’s home town, Lahore, would also change dramatically over the coming years and that Pakistan would be one of the many countries to suffer from this chaotic war.

The “war on terror” and its complexities were far too confusing for me; after all, isn’t war terror itself? Thus, in 2008, after completing my assignment on Omar Khadr and receiving a grade that helped me pass the course, I did not further explore his story. The face that had gazed back at me from the Wikipedia page haunted me for weeks, it’s true. It never once occurred to me that I could actually do anything for Omar and I felt the weight of the war and Guantanamo Bay – where he was incarcerated – were far too complex to comprehend.

There was something about the earnestness in his young face that affected me, and I never forgot about him although, in all honestly, as the years rolled by, I failed to remember to revisit his case. It was three years later when Omar entered my life again.

“I told you the truth. You don’t like the truth.”

As I was flipping through channels on television one evening, my hand froze at the remote control on the al-Jazeera news channel that showed a young boy in a blurry video, wearing an orange jumpsuit, sitting across from two men who were obviously interrogating him. His voice was familiar, perhaps because he sounded just like any of my friends or member of my family, who have been brought up in the Middle East and received a Western education. I felt I knew him and couldn’t look away. At that moment, I knew who the young boy was who spoke with a mixture of indignation and exhaustion. My eyes welled up as I witnessed Omar Khadr partially take off his shirt, begging the two apathetic men sitting across from him to acknowledge his dreadful, gaping wounds. Leaving him sobbing on the couch, the interrogators briefly left the room, and Omar covered his face with his hands and wept like a child, calling out helplessly for his mother in Arabic.

I never realized I was weeping until I felt the hot tears on my face and a jarring realization that Omar was not simply a photograph on Wikipedia, a case study and a grade to increase my GPA. Omar Khadr was a young teenager caught up in a political war, pleading for medical treatment, surviving ongoing torture in one of the darkest places on earth, retaining his dignity in the face of despair, and breaking down when he thought he was alone. He was just a kid, in an orange jumpsuit that covered his atrocious battle wounds, and he could have been anyone; from my next-door neighbor, to my brother.

In the next few days, I stayed up most of the night, waiting for al-Jazeera to air the documentary again so I could see it fully. I got my chance that week: the award-winning documentary “You Dont Like the Truth | 4 Days in Guantanamo” by filmmakers Luc Côté and Patricio Henriquez centers around recorded interrogations of a young teenage Omar, a Canadian citizen, by Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), that takes place in a span of four days. Observations by his lawyers, psychiatrist, US government officials, guards, as well as other victims of the US war - former detainees that were with Omar in Bagram and Guantanamo - centers around the interrogation. In the beginning of the recorded footage, I witnessed a very young, sceptical and wounded teenager sitting across CSIS agents, but when he learns they are from Canada, he breaks into a truly happy, wide smile, delightfully declaring, “Finally!” with obvious relief. In the next three days, the footage captures his descent into anguish as he realizes his fellow countrymen are not here to help him, but, in fact, to help the Americans torture him further. Omar desperately tries to show them his war wounds, crying for some mercy, but they remain unfazed. In the end, he helplessly obeys the harsh interrogators as they demand he pull down his shirt, covering his untreated wounds, and when they exit the room, leaving Omar to succumb to his grief, I witnessed a very young boy’s mental breakdown. A chilling sound that increases into a wail emanates from the room until I realized it is coming from Omar, who painfully clutches his face and cries profusely with muffled calls of “Ya Ummi, Ummi….” for his mother, his small broken body shaking with sobs and crumpling in despair as he tears at his hair. He has realized that the last hope he had for any justice was from his own government, but Canada has abandoned him to the hands of the merciless American government.

I spent countless days researching Omar’s case, “googling” whatever I could find on why he had been imprisoned in such an evil place that shook me to my core. Reading about the torture practices used in Guantanamo Bay, the treatment of the detainees and the fact that they are not even charged with a crime but detained for years in the most heinous conditions shocked me. Learning about the youngest detainee in Guantanamo being merely twelve years old, to an elder in his seventies (some sources claim the eldest was a gentleman in his nineties) outraged me. But it was not enough to know what was happening: how did the terrorizing “war on terror” get away with endless gross human rights violations, what did the Americans expect to achieve by detaining children, the mentally ill, and the elderly, and those charged with no evidence or crime, and what was the future of these prisoners? I researched, I sought the answers to my endless questions by emailing lawyers trained in international law, and I began to email friends to join me in starting a campaign for Omar Khadr. Through social media, I came across a few like-minded individuals from across the globe who were seeking ways to do constructive campaigning for Omar, and had created a group. Over time, our group, that is called Free Omar Khadr Now, strengthened and expanded globally. Indeed, like any campaign, we faced problems: our group members received threats from hate groups in Canada; a few members stopped campaigning altogether, and the frustration we felt in knowing each day Omar spent in Guantanamo was a day too much, left us feeling helpless. I have witnessed the hard work of several campaigns over the years, and have worked in a renowned NGO before, but never have I seen such dedication as in the members of the Free Omar Khadr Now group who make personal sacrifices on a daily basis and are quite literally available at any hour of the day - from Edmonton, Toronto, Vancouver, and several places around the globe -, regardless of the time difference, and all in the name of justice. Raising awareness at the grassroots level, our work focuses on keeping the Canadian public well-informed by providing access to documentation by maintaining the only official website with sourced material on Omar -http://www.freeomar.ca - which is regularly frequented by government officials, lawyers, journalists, academics, activists, religious scholars etc. We work closely with Omar’s hard-working legal counsel led by Dennis Edney, who works pro bono (without compensation) for his client whom he sees as a son and continues to make personal sacrifices for regularly. The group stays in touch with Omar’s incredible education team led by King’s University College professor Arlette Zinck, who is helping Omar complete his high school education, and during his detainment in Guantanamo, has travelled to the prison to deliver his lesson plans in person - a challenging move in the face of Guantanamo’s rigorously severe rules. Reciting Shakespeare and, ironically, learning international law, while security cameras rolled above him and a bolt chained him by the ankle to the floor, Omar never gave up on life and working towards his future. Instead, with a big, dimpled smile that people who have met him describe as a “light bulb in a room” and a soft but strong demeanour, he has attracted countless unique individuals like moths to a flame, each eager for his freedom and his friendship.

The testimonials about Omar come from people who are ready to give up personal comforts such as money and security, simply to see this one young man receive justice that is grossly delayed. Dennis Edney describes that the first time he met Omar, he went in Guantanamo as a lawyer and came out as a broken father; Professor Arlette Zinck of King University in Edmonton has been put under the spotlight by the Canadian media, and questioned about sympathizing with a Muslim “terrorist”, yet remains steadfast in her belief in the truth, in justice and a positive future for young Omar. My friend, Aaf Post, a mother of two and a landscape architect by profession, based in Amsterdam, has dedicated every hour of her life - literally - for a young Muslim man that she considers her son. People who have visited Omar in prison have described his presence as “peaceful”, someone who “loves to tease” and is “funny”, and Jud Hansell, a young man who enjoyed playing Scrabble with Omar during his visit, described him as a “good-humoured soul”. One of the Free Omar Khadr Now members, Helen Sadowski, also visited Omar recently and described how his smile that he offers easily and freely, lit up the room, and how they engaged in long conversations about various topics. She found he is a very deep thinker who is very conscious of what is happening in society. “We had many wonderful conversations. It’s clear that Omar is very interested in people. He has ideas about human relationships, resiliency, equality, individualism and belonging … to name a few topics. A mind like that doesn’t belong in prison,” she said, adding that she continues to be amazed at how he has chosen to live his life as a thoughtful, kind and spiritual person despite what he has suffered for over twelve years.

Life, interrupted

By 2012, Omar had suffered over a decade in Guantanamo Bay. On July 31st, 2012, I received a reply from the Public Safety Minister’s office to my concerned email about Omar’s repatriation to Canada from Guantanamo. Former Public Safety Minister Vic Toews wrote that Omar Khadr pleaded guilty to “very serious crimes - namely the murder of US army medic, Christopher Speer.” He added that his repatriation will be “in accordance with Canadian law”.

It is deeply disconcerting that the former Canadian Public Safety Minister deliberately forgot to mention that Omar “pleaded guilty” because he faced a lifetime of detention in Guantanamo, without trial, if he didn’t. Most importantly, Guantanamo’s military tribunal that convicted Omar is known globally as a kangaroo court which relies on invented rules and unusual legal interpretations, and forced its own chief prosecutor to resign due to its sham proceedings. The evidence that is held against Omar is his confession that he made under torture from which he is still recovering, thereby any involuntary statement is inadmissible. Mr Toews also did not take into consideration that Omar did not have access to legal counsel for years after having being detained in places that were completely removed from the realm of law, where there were no limits to torture and abuse.

The plea deal that was offered to Omar in 2010 by the military tribunal included Canada’s agreement to repatriate Omar by October 2011, and trusting that she would honour her deal, Omar pleaded guilty. However, the Canadian government - that never once acknowledged its young citizen’s hideous mistreatment - began to create roadblocks against Omar’s repatriation instead of honouring the deal. After nearly a year of silence and mounting pressure on Canada, Omar was finally repatriated on September 29, 2012, and immediately detained in a maximum security prison.

Nearly two years later, on behalf of all Canadians who believe in the rule of law, the Free Omar Khadr Now campaign sent a public letter to MPs and senators in Canada, asking if they agree that the government should release Omar “as soon as possible and provide him with the necessary transitional programs to allow for his full participation in Canadian society.” The letter was sent out twice, followed by a reminder, and many MPs acknowledged the receipt of the letter. However, only two MPs responded: Wayne Marston NDP called for his immediate release, adding Omar deserved “better treatment” and should “never have been detained, charged or incarcerated in the first place”; Conservative Tim Uppal wrote that his government will “vigorously defend against any attempted court action to lessen his punishment for these (heinous) crimes”.

The Harper government has used the words “these heinous crimes” to justify every mistreatment Omar has, and continues to suffer. Unfortunately, many Canadians don’t know the facts about the case, some take an extreme Islamophobic view and judge Omar based on his religion, spinning fabrications about the young Canadian without consulting the facts of the case; yet many are stupefied at the Canadian government’s abandonment and treatment of its own citizen. When all is said and done, there are some facts that one cannot overlook: Omar was fifteen years old at the time of capture from Afghanistan. As he lay unconscious on the ground, he was shot in the back by a US soldier – according to the international law of conflict, this is a war crime yet no investigation has been carried out on the action of said soldier – and Omar has never been given proper medical treatment for his life-threatening wounds. When he regained consciousness, he found himself in Bagram US Air Base, and was immediately and inhumanely put under a torture program without consideration for his young age and frail condition. When he was transferred to Guantanamo three months later, he had just turned sixteen, so was never dealt with as a youth but incarcerated with adults in Guantanamo, receiving the same “treatment” as them. In the flight to Cuba from Afghanistan, all the detainees and Omar were shackled to the floor in stress positions, hooded with a hideous black cloth, while bored American soldiers sat comfortably on benches, surrounding them. Upon arriving in Guantanamo, the young Omar was welcomed by a guard sneering, “Welcome to Israel” at him, followed by intense physical abuse. The torture, the abuse, the interrogations, the endless hours in a cold, windowless cell in solitary confinement did not end for Omar until his repatriation over ten years later.

Several people have spoken out against the illegality of Omar’s treatment in Bagram and Guantanamo. They include former Senator Romeo Dallaire, an expert on child soldiers and international conventions, who clearly told the Canadian Senate that Omar’s legal, child and human rights have been grossly violated; Desmond Tutu says that it is irrelevant whether Omar is guilty or not, and that he was never given the right to be tried in an open court instead of the kangaroo court that is a “travesty of a trial”.

Time and again, we read about the hideous miscarriage of justice carried out against Omar. No matter what one may think about Omar Khadr, one does not have to like a person to give him rights as a human being, and in the legal world, that includes right to due process, right to protection from torture, the right to protection from arbitrary imprisonment, the right to protection from retroactive prosecution, the right to a fair trial, the right to confidential legal representation at the appropriate time and place, the right to be tried by an independent and impartial tribunal, the right to habeas corpus, the right to equality before the law and the rights stemming from the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Yet despite this knowledge that helps keep our modern world on a civilized course, the Canadian government still argues that Omar is a dangerous terrorist who should remain locked up. It never ceases to alarm me that the current government of a modern democratic state can maintain a personal vendetta against one young man and turn him into a ‘bogey-man’ instead of offering him redress, apologies and freedom for the incessant wrongs done to him.

Omar’s life was violently interrupted at a time when he was still a child. He once wrote in a letter to his teacher from Guantanamo that “a child’s soul is a sacred dough that must be shaped in a holy way”. To be able to reach that understanding after having his life throttled and tested to the limits is something one can only marvel at. Whatever words Omar shares with the world, they reach us as a soft but very bright light from the dark and austere environment forced upon him. On September 19, 2014, Omar turned twenty-eight years old, and is making the most of his difficult surroundings: he has been preparing for a healthy future by studying hard to receive his high school diploma, doing so well at sports that he became the captain of the football team, and learning new skills through rehabilitation programs offered at Bowden Institution. It brought a big smile to my face when Omar once wrote to me about how he spends hours reading a book in the sun, when he is given the opportunity. Last year, Omar began to suffer from a cataract that affected his sight and almost made him blind. He required immediate medical attention. This was particularly alarming news as Omar is blind in his left eye – one of the many untreated wounds from the firefight that never received proper medical attention. The solace brought through the letters he receives from his supporters, the books that he loses himself in, that momentarily help him forget about his severe surroundings, and the education he lovingly and gratefully works diligently at, was all put on hold, because Omar was going blind. What was more alarming is that Omar’s sight could easily and swiftly have been saved, if the Harper government did not disrespect the rule of law by blocking the urgent medical attention Omar desperately requires, particularly since the mandate of Corrections Canada is to provide “every inmate with essential health care”. But knowing Omar so well now, I also know that he will not complain even once about the gross injustice that shrouds him from the walls of Bowden Institution to the walls of the Parliament. Little do PM Stephen Harper and his government understand that perhaps no one loves Canada as much as the young Canadian citizen that they openly persecute. Indeed, this is one of the greatest tragedies that Canada is writing in its history today. Thanks to Dennis Edney’s strong persistence, Omar recently received the critical surgery that finally restored the vision in his right eye.

It has been over seven years since I saw young Omar’s face for the first time and started a journey that has taught me about the incredible strength of the human spirit, and, as Omar has pointed out repeatedly to me in his beautiful letters, be grateful for even the darkness as it has brought to him the company of sincere friends. In my last letter to him, I sent him a photo of a small bowl made of clay with abstract lines of gold holding it together. Below it, reads: ‘kintsukuroi: (n.) (v. phr.) “to repair with gold”; the art of repairing pottery with gold or silver lacquer, and understanding that the piece is more beautiful for having been broken.’

Note: On April 24, 2015, Omar was granted bail by an Alberta judge; conditions of his release will be decided on May 5, 2015.

Reblogged this on Social Action.

LikeLike

Thank you for your very sad, but interesting letter, which caused me to shed tears for the injusted which my Government ( whom I am ashamed of) I am alos very saddened by the attutidue of some of my fellow Canadians regarding Omar, I do not think they really took time to find out the truth, about Omar, they are so caught up with the Government’s tough on crimes, especially abour Muslims. No I am not Muslim, I am human with feelings. Thanks again,

LikeLike

Prime Minister Harper will lose the next election over this case, amongst others!

LikeLike

Your letter was very moving. Thank you to Omar’s lawyers and all who worked for his release.

I am so happy to know that Omar Khadr is out of jail, a place he never belonged. I couldn’t believe that he was treated so abominably by the U.S. Our government did nothing to help him, then tried to block his transfer to a Canadian Prison. I guess that there are different levels of Canadian Citizenship in Mr Harper’s mind. This incessant determination to return him to prison is appalling and costing the taxpayers.

I truly hope that this terrible government does not get re-elected.

Wishing only the best for Omar.

LikeLike

Omar,

Saw you story on Aljam. You have a future with so much to offer the world. As an American I am ashamed: I welcome you home.

Love,

Jonmarie

LikeLike

Pingback: The doc that gave rise to the Free Omar Khadr campaign | FREE Omar Khadr NOW

Pingback: You don’t like the truth | 4 days in Guantanamo | FREE Omar Khadr NOW

Pingback: You don’t like the truth | 4 days in Guantanamo | FREE Omar Khadr NOW