Monday, 22 October 2020 08:21 | Written by Catherine Morris

The Canadian government has claimed Omar Khadr had the benefit of due process in the United States.

His return to Canada on Sept. 29 prompted yet more official statements and headlines labelling him a war criminal and a convicted terrorist. These assertions distort and contradict both the facts and the law.

As a result, many people hold an erroneous belief that Khadr pleaded guilty to legitimate charges in a properly constituted court. In fact, Khadr was never charged with any U.S. criminal offences or international war crimes.

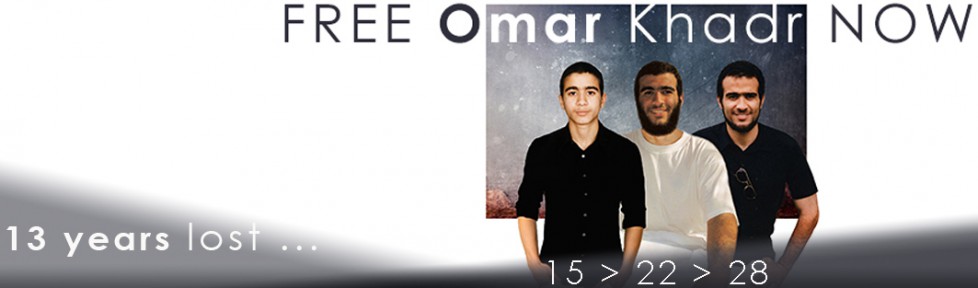

After his 2002 capture on a battlefield in Afghanistan at age 15, Khadr waited more than three years before facing charges at a military tribunal set up by an executive order of former president George W. Bush’s administration.

In 2006, the U.S. Supreme Court in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld found the tribunals to be unlawful and in violation of the Geneva Conventions.

The U.S. Congress hastily passed a new Military Commissions Act and Khadr was recharged with newly created offences even though international law and the U.S. Constitution forbid prosecutions for ex post facto offences, as does Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The military commission procedures provide for relaxed rules of evidence and permit coerced evidence not allowed by U.S. or Canadian criminal law.

Evidence obtained in violation of the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment can also be admitted because of the Military Commissions Act’s narrow definition of torture that’s at odds with the convention. Nor is the military commission viewed as independent.

In June 2007, Col. Peter Brownback, then the military commission’s presiding officer, dismissed the charges against Khadr. He said that while the commission had jurisdiction over unlawful enemy combatants, prosecutors had failed to prove Khadr had taken up arms against the United States unlawfully.

A quickly convened military commission review overturned that decision in September 2007 and reinstated the charges.

Brownback acknowledged he took heat from the Pentagon for dismissing the charges. In June 2008, Brownback threatened to suspend the proceedings against Khadr unless prosecutors handed over Khadr’s medical and interrogation records. Later that month, the Pentagon replaced Brownback.

In May 2008, the Supreme Court of Canada in Canada (Justice) vs. Khadr ruled that participation by Canadian officials in the process in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, was contrary to Canada’s binding international obligations.

In January 2010, the top court in Canada (Prime Minister) v. Khadr denounced Canadian officials’ violation of Khadr’s s. 7 Charter rights.

The top court declared Khadr’s entitlement to a remedy but left it up to Canada’s executive to decide how best to respond. Canada’s response was a diplomatic note asking the United States not to use information turned over by Canadian agents.

In July 2010, Canada’s Federal Court in Khadr v. Canada gave the government seven days to supply a list of all possible remedies to cure the continuing Charter violations. The House of Commons standing committee on foreign affairs had already made one recommendation in June 2008 that Canada secure Khadr’s repatriation.

Majority votes of the Senate on June 18, 2008, and the House of Commons on March 23, 2009, had urged repatriation. Instead of suggesting remedies, the government appealed the ruling on the seventh day.

Predictably, the Guantanamo Bay military commission ruled all of Khadr’s statements admissible, including those made as a result of treatment that violated the convention against torture, in August 2010.

Radhika Coomaraswamy, then the United Nations special representative for children and armed conflict, pointedly stated that in international law, child soldiers “must be treated primarily as victims and alternative procedures should be in place aimed at rehabilitation.”

Canadian officials paid no attention. Instead, they agreed to Khadr’s October 2010 plea bargain and said Canada would be “inclined to favourably consider” repatriation to Canada after a year of his sentence.

Lawrence Cannon, then the foreign minister, promised the House of Commons that Canada would implement the agreement. The year came and went.

In June of this year, the UN committee against torture urged Canada to repatriate Khadr and to redress the human rights violations found by the Supreme Court. Minister of Public Safety Vic Toews responded by complaining that “when there are serious concerns regarding human rights violations across the world, it is disappointing that the UN would spend its time decrying Canada.”

Khadr has never faced a trial before any properly constituted court that afforded the judicial guarantees recognized in international law as indispensable to fair proceedings.

This is in direct violation of the Geneva Conventions. In addition, the case demonstrates serious and flagrant violations of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the convention against torture, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and the protocol on children in armed conflict.

We must view the voluntariness of Khadr’s plea bargain in the context of the U.S. policy of holding Guantanamo Bay prisoners until the end of the so-called war on terror. Without the deal, Khadr faced indefinite detention whether the military commission found him guilty or innocent.

This catch-22 followed eight years of detention marked by denial of virtually all of his rights. They included the rights to habeas corpus, access to an independent tribunal for determination of rights, proper legal representation, family visits, and freedom from torture and other cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment.

Such conditions defy the very concept of voluntary negotiation. The U.S. plea agreement is not a reliable indicator of guilt in or out of court.

Some Canadians have expressed fears about public danger. Safety is an important consideration that is served only when facts and law are respected. Public safety is at risk in a polarized climate of suspicion, fear, and hatred fomented by public officials’ derogatory characterizations of Khadr.

Toews is responsible for Corrections Canada as well as appointments and renewals of adjudicators at the Parole Board of Canada. It is improper for a minister to make statements about Khadr that could influence the impartiality of adjudicators at tribunals vested with the responsibility for independent determinations.

The Khadr case raises concerns about disrespect by Canadian government officials for our courts, the UN human rights system, and, indeed, the rights of all of us. Canadian ministers and officials must start treating Khadr in accordance with Canadian and international law.

Catherine Morris teaches international human rights at the University of Victoria. She also teaches courses in negotiation and conflict studies at universities in Europe and Asia. In addition, she monitors human rights in several countries for Lawyers’ Rights Watch Canada.

Source: http://www.lawtimesnews.com/201210229386/Commentary/Speaker-s-Corner-Officials-must-stop-demonizing-Omar-Khadr