“Now that Khadr is back in Canada, the government should do all possible to help rehabilitate and reintegrate him back into society. Canada is obliged, under the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict, which it ratified in 2000, to provide “all appropriate assistance” for the physical and psychological recovery of former child soldiers.”

The US accused Khadr of throwing a grenade that killed US Army Sergeant First Class Christopher Speer and injured two others. He was charged with murder and attempted murder in violation of the laws of war, conspiracy to commit terrorism, providing material support for terrorism, and spying.

In spite of Khadr’s young age at the time of his capture, the United States refused to apply universally recognized standards of juvenile justice in his case, or even to acknowledge Khadr’s status as a juvenile. Both US and international law allow for detention of juveniles only as a last resort, require juveniles to be provided educational opportunities and housed separately from adults, and mandate a prompt determination of all cases involving children. Yet Khadr was incarcerated with adults, reportedly subjected to abusive interrogations, and not provided with any educational opportunities (unlike other children at Guantanamo). In addition, he was detained for more than two years before he was provided with access to an attorney, and for more than three years before he was charged. He was initially charged in the first round of military commissions, which were ultimately struck down by the Supreme Court. Another two years passed before he was re-charged before the current military commissions.

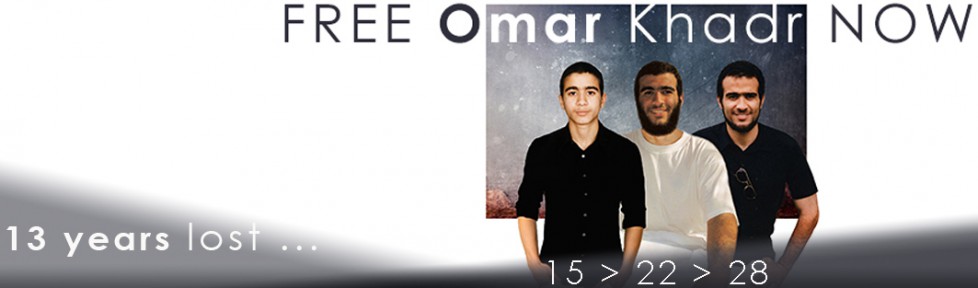

In October, 2010 Khadr accepted a plea deal. Under the terms of the deal, he was to serve eight additional years in custody, with the right to apply to transfer to Canada after serving one year in Guantanamo. In a series of diplomatic notes between the US and Canada attached to his plea agreement, Canada agreed to favorably consider his application for transfer. However, Khadr was not transferred to the custody of the Canadian government until September 29, 2012, nearly two years after being sentenced. Khadr will be eligible for parole after serving one-third of his sentence, or 32 months, meaning he could be released as early as June 2013. Canada is obliged, under the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict, which it ratified in 2000, to provide “all appropriate assistance” for the physical and psychological recovery of former child soldiers. Now that Khadr is back in Canada, the government should do all possible to help rehabilitate and reintegrate him back into society.