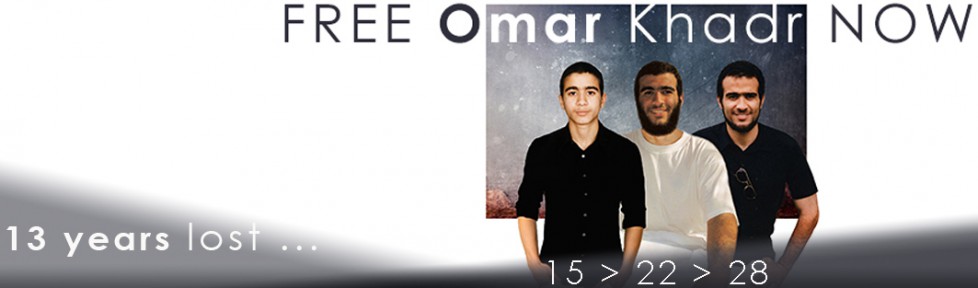

Omar Khadr, a Canadian and Guantánamo Bay’s youngest prisoner, is 26 today. Torture, abuse and a decade of continuing arbitrary detention, however, offer little to celebrate.

Demonstration in London during Omar Khadr’s 2010 military trial

Only 15 years old when he was captured by American forces in Afghanistan on 27 July 2002, following a battle between American soldiers and local militias, he was found unconscious, blinded in his left eye and was shot twice in the back. Inadequate treatment for his injuries at the time means that he continues to suffer pain both in his back and his eyes and has limited use of his left arm. He currently risks losing his sight altogether.

Prior to being taken to Guantánamo Bay, he was imprisoned at Bagram in Afghanistan for three months, where he was threatened with rape and other forms of physical and psychological abuse. This included waterboarding: a letter last year from US army psychiatrist Brigadier General (retired) Dr Stephen Xenakis to the Canadian government states that the 15-year old Khadr “[…] was mocked and remembers having water poured over his face while hooded so that he felt unable to breathe.” One of his first interrogators at Bagram, Joshua Claus, was later convicted of prisoner abuse and in relation to the prisoner deaths at Bagram featured in the Oscar-winning film Taxi to the Dark Side. Omar Khadr also reported that his interrogators told him he could go home if he confessed to the charges made. These “confessions” obtained from a child through torture would later constitute part of the evidence against him at his military tribunal.

At Guantánamo, he was treated as an adult and subject to the same treatment, including prolonged periods of solitary confinement. The US’ attitude to child prisoners at Guantánamo is hardly surprising given its status as the only country in the world, apart from Somalia, not to have ratified the International Convention on the Rights of the Child. It has, however, signed and ratified the Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict, published in the same month that Khadr was captured; Article 7(1) states that “State Parties shall cooperate […] in the rehabilitation and social reintegration of persons who are victims of acts contrary to this Protocol.” With the international outcry and response to the viral Kony 2012 campaign, both in the US and beyond, it is unfortunate that the same interest has not been shown in the US’ child prisoners of war.

Furthermore, in 2010, he was tried at the first military tribunal at Guantánamo Bay since President Obama took power and is the only person to have been tried as an adult before a military tribunal for war crimes allegedly committed as a minor since World War II. Anthony Lake, UNICEF Executive Director warned that his trial could set “a dangerous international precedent for other children who are victims of recruitment in armed conflicts.” Ironically, at the same time as Khadr’s trial, when he was aged 23, an 88-year German former Nazi prison camp guard was charged in a German youth court for alleged involvement in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Jews at a concentration camp during World War II; in spite of his age at the time of the charges, and dying later that year before trial, a youth court was considered appropriate as the charges related to offences that occurred in 1942 when he was 21, and thus legally considered a minor.

In Omar Khadr’s show trial, on the other hand, at pre-trial hearings where US interrogators admitted that they used threats of rape and murder to extract confessions, the defence’s motion to have torture evidence disallowed was dismissed. In October 2010, in a secret plea bargain, Omar Khadr pleaded guilty to throwing a grenade that killed an American soldier and wounded another in the gun battle he was captured in. Otherwise facing the prospect of at least a life sentence if found guilty, as part of the plea deal, he would have his sentence slashed to just eight years of which he would serve the final 7 years in his native Canada. Omar Khadr has been due for release since October 2011; his return home is almost a year, if not a whole decade, overdue.

So, why does the story not end there with Khadr repatriated late last year? For its part, the US is keen to see Khadr go. Having abused just about all his other rights, this is not due to any altruism or newly-discovered goodwill, but expediency: the fear that the delay in honouring its deal could deter other prisoners from entering similar plea bargains, on the basis that they may not be released eventually.

The hold-up appears to come from the other side of the border in Canada. Canada’s liberal image faded soon after 9/11 with tightened security measures and revelations of its collusion in the extraordinary rendition of Canadian citizen Maher Arar to Syria. In Omar Khadr’s case, the Canadian authorities washed their hands of their obligations years ago. Having had opportunities to interrogate him at Guantánamo Bay, Canadian intelligence officers handed the information they learned from him to the US military to use as evidence in his military commission. In 2008, a video from 2003 was released showing Omar Khadr being questioned by Canadian agents following sleep deprivation, a form of torture.

Canadian lawyers for Khadr brought a lawsuit against the government to force it to demand his immediate repatriation, which resulted in a Canadian Supreme Court ruling in January 2010 that the government had violated his fundamental human rights under the Canadian constitution, but stopped short of ordering the Canadian government to demand Omar Khadr’s return to Canada. Condemnation of the Canadian government’s stance has come from all quarters, particularly human rights NGOs and recently, the UN Committee Against Torture demanded that the country seek his immediate repatriation.

Over the past year, Canada’s inability to repatriate one citizen (or indeed, write one letter seeking his repatriation) has become a shameful and drawn out saga. While not a party to Omar Khadr’s plea bargain, the Canadian government is well aware that it was based on an understanding that as of November 2011, he would be eligible for transfer back to Canada. According to Amnesty International UK, “The Government of Canada acknowledged and accepted that transfer was integral to the plea deal by means of a diplomatic note provided to the US government at the time. In November 2010 former Minister of Foreign Affairs Lawrence Cannon stated that “we will implement the agreement that was reached between Mr. Khadr and the government of the United States.””

Anticipating this release date, Khadr’s Canadian lawyers formally applied for this transfer in early 2011. The US met all of Canada’s conditions for Khadr to be released by April 2012 and has since been awaiting a letter from the Canadian Minister of Public Security Vic Toews seeking Khadr’s return. In a letter to the Canadian government in July, American NGO Human Rights Watch accused the Canadian government of being “responsible for every additional day [since April 2012] Khadr spends in Guantanamo.”

With the US government’s willingness to return Omar Khadr, it was anticipated he would be released by the end of May. Four months on, he is still in Guantánamo Bay. Accusing the Canadian government of “stonewalling” on Omar Khadr’s case, his lawyers brought a case against the government in June to force it to seek his immediate repatriation. The case is still pending.

Around the same time, in early July, Senator Roméo Dallaire, a staunch supporter of Omar Khadr and advocate for child soldiers, launched a petition demanding the Canadian government fulfil its obligations to Omar Khadr and its deal with the US concerning his release:http://www.change.org/omarkhadr The petition can still be signed, and with just over 30,000 signatures three months later, from all over the world, it paints a damning picture of public apathy. That a senator need resort to a public e-petition website to communicate with his government speaks volumes about the level of debate on this matter and the state of democracy in Canada. However, Sen. Dallaire, a retired general and head of the failed UN mission to Rwanda during the genocide there, is no stranger to the fact that those in a position of authority who are able to make a difference will all too often choose to do nothing at all.

Vic Toews response has been to write to the US authorities seeking videos and psychiatric reports to check whether Omar Khadr is fit to return to Canada: yet more foot-dragging. Vic Toews received those documents and videos earlier this month and now only has to make his assessment and decision. According to a report in the Huffington Post, Khadr’s transfer will be approved and he will return to Canada before the US election in November. Vic Toews has dismissed this as untrue and instead the Canadian government has accused the US of stalling the process.

In view of the vitriolic, right-wing campaign in large parts of the Canadian press against Khadr over the past few months, there is a good chance that he will return to the country soon. In the UK, where several former prisoners were charged but never convicted, similar pre-emptive media smear campaigns also greeted their return. There has been no “recidivism” in Britain.

After a decade in Guantánamo Bay, Omar Khadr is no doubt damaged by his experiences, which have been unnecessarily prolonged by his own government. Summing up his analysis of the 300+ hours he spent in interviews and assessments with Omar Khadr, Dr Xenakis stated: “I have not observed any indication of aggressive or dangerous behavior by Mr. Khadr since I first met him in December 2008. He is a considerate and thoughtful young man who has consistently emphasized his goal to establish a constructive and peaceful life as a Canadian citizen. He has not given any indication at any time of presenting a personal or national security threat.” Along with many other organisations and individuals, Dr Xenakis also advocates rather than further incarceration upon his return to Canada, particularly in view of the time he has already spent in prison, Omar Khadr should be rehabilitated and not face further detention.

What Canada has to do has long been obvious, the question is simply why has it not?

For a case background: http://www.cba.org/cba/advocacy/pdf/khadr.pdf

http://www.youdontlikethetruth.com/

September 19, 2020 · by Aisha Maniar · in human rights

Well done to everyone at Free Omar Khadr and everyone else around the world who have worked so hard for Omar’s return to Canada today! Let’s hope this is where his ordeal ends.

Alas, 160 odd prisoners remain at Guantánamo and the penultimate prisoner left in a body bag…

LikeLike